© Wikimedia Foundation

Disappearing salmon

A decline in salmon stocks is affecting the Saami way of life

Fishing restrictions in the small town of Ohcejohka (Utsjoki)—Finland’s northernmost municipality—are affecting food security in the region along with the ability of Saami elders to pass along their traditional knowledge. A salmon fisher and teacher from the village of Njuorggán (Nuorgam) in the municipality of Ohcejohka, ÁSLAT HOLMBERG is also president of the Saami Council and a former member of the Saami parliament of Finland. The Circle asked him to describe the situation for the 1,200 people who call Ohcejohka home.

I’m what you would call a traditional fisher, which means I fish with nets. I grew up fishing salmon in the Deatnu (Teno) River near Ohcejohka and knowing there would always be salmon in our freezers. Salmon is a building block of my culture.

But our access to salmon changed in 2017, when the Finnish and Norwegian governments shortened the fishing season and limited the number of days we could fish on the Deatnu River. This decision was made in response to diminishing salmon stocks.

© Áslat Holmberg

Where did all the salmon go?

It’s not clear what caused the decline, but it’s likely that climate change is a key driver: some of the stocks that salmon feed on may have migrated further north due to warmer waters. In the Finnish side of Sápmi, the average temperature has risen by more than 2°C over the last century or two. It’s also possible that the salmon can’t find enough food and are just not returning in the same numbers.

But it’s interesting that the number of juvenile salmon in the river has not declined as steeply as the number of returning salmon. What that tells us is that they are just not coming back. Atlantic salmon almost always come back to the river where they spawn—so it’s likely they are not surviving their ocean migrations. We don’t know why.

In any case, in 2021, a total fishing ban was imposed, and it is still in place, so we have not been able to fish salmon at all for two summers in a row. The ban applies to the Deatnu River, its tributaries, estuaries and the Finnmark sea areas from May to December. And the authorities have proposed extending the ban again next summer.

Consequences for Saami people

This has huge impacts for Saami in the area. Most of us grew up with the idea that salmon are the core of our food security. Its absence means a key food source is now “off the menu,” so to speak. It is also having huge economic and cultural impacts.

Ohcejohka used to be a popular destination for tourists who wanted to try salmon fishing. But for two summers now, the tourists have not shown up. It’s estimated that we are losing about five million euros per year due to the ban. This has driven the municipality into a grim situation where it doesn’t have the money it needs to fund some of its basic needs.

Culturally, our traditional knowledge is tied to fishing, and when you’re not able to fish, you can’t transfer that knowledge. For example, net fishing requires knowledge about how to fish, when to fish, what kind of equipment to use, how to repair that equipment, and even how to make the equipment in the first place. If we can’t fish, we can’t pass this knowledge along to the next generation.

And given the age of some of our elders—my father will turn 90 next summer—even two summers is a long time. Not enough youth have had the chance to acquire these skills, so every year that goes by is valuable in terms of learning from the older generation. The declining salmon stocks and resulting bans threaten the continuation of our culture and the knowledge it contains.

A complex problem—and a rights discussion

But even our traditional knowledge does not really help us understand the root of the problem. That’s because the biggest changes have happened in the ocean, not in freshwater—and the ocean is an immensely complex ecosystem. Of course, we could still propose management strategies, like quotas on the fishing of species that salmon feed on or tighter regulations for the salmon farming industry, which is the number one threat to wild salmon. Indigenous knowledge also tells us that increased fishing and hunting of salmon predators would help. But other than that, it comes down to mitigating the effects of climate change.

As a person who relies on salmon and is personally connected to the ocean, I find the future very worrying.

Yet we have to find a way to consider the rights of Saami people, which are closely linked to the ecological situation. Salmon is fundamental to us as a food source, so we need to look for ways to maintain our knowledge and culture despite the dire situation. One approach could be to look at the types of salmon stocks in the watershed, see which ones are doing better than others, and figure out what amount of fishing could be allowed for the healthier stocks. We should also be looking at ways to strengthen the environmental conditions for the salmon, both in the freshwater and the sea.

Compounding the problem, we are also now dealing with an invasive species. Pink salmon (also known as Pacific or humpback salmon) have essentially overtaken the river—last summer, there were four times more pink than Atlantic salmon. This changes the very nature and composition of the river, including its nutritional load, because pink salmon die after spawning, and it’s estimated that next summer, there could be half a million of them in the river.

You might wonder if these pink salmon could not become a food source for us. Perhaps that could be one way of adapting, but we have not been able to try because of the fishing ban. I’ve heard that next summer, some amount of pink salmon fishing may be allowed—but the challenge is that the same equipment used to catch them would also catch Atlantic salmon.

As a person who relies on salmon and is personally connected to the ocean, I find the future very worrying.

© Ketill Berger / WWF

A DECLINE AND AN INVASION

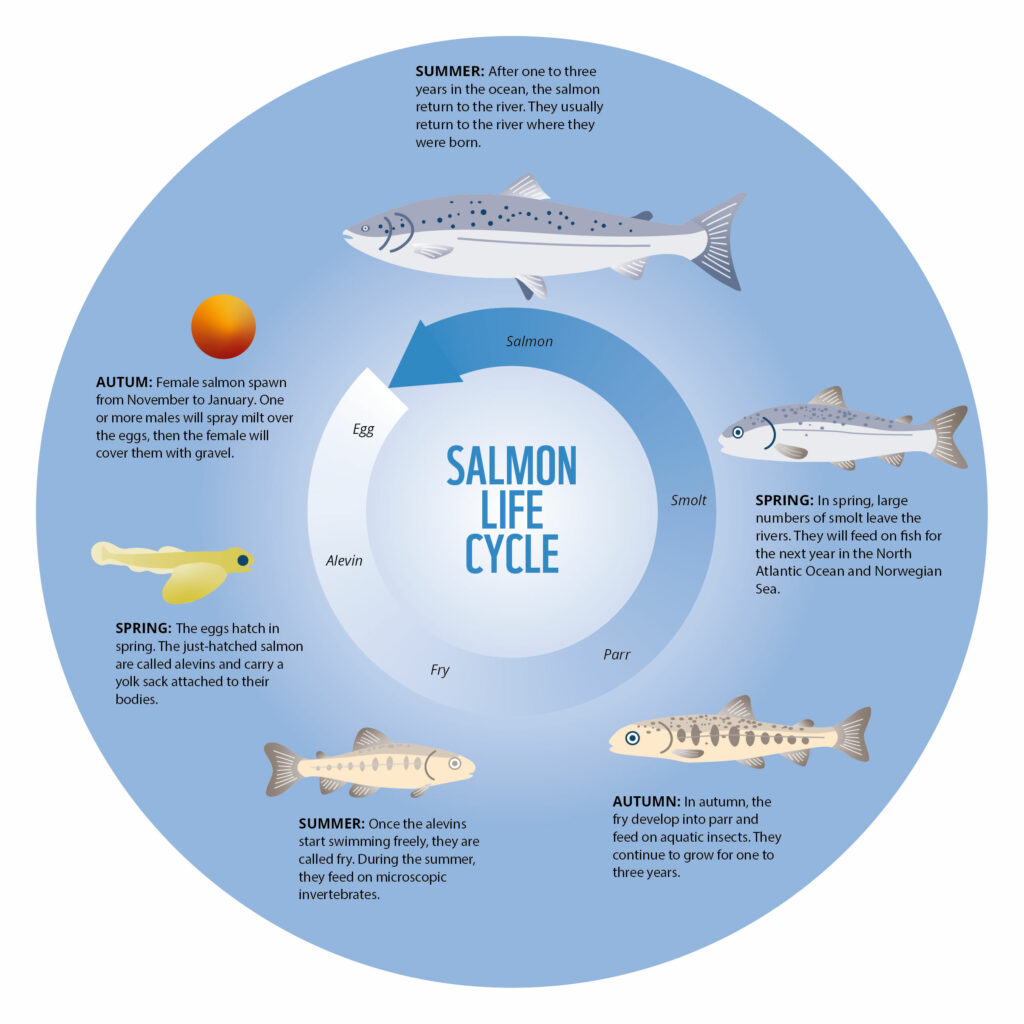

Atlantic salmon are born in streams and rivers and migrate out to the open sea, returning to freshwater again to reproduce.

The Deatnu River near Ohcejohka (Utsjoki) flows into the Arctic Ocean and has traditionally been one of Europe’s largest salmon rivers. But in recent years, there has been a devastating and poorly understood decline in the salmon population in the region.

Meanwhile, invasive pink salmon have begun showing up by the thousands, setting off alarm bells. The fish were first introduced in the 1950s by Russian researchers, who released them on the Kola Peninsula. The salmon spread moderately at first, but their population in the Deatnu River exploded in 2019 and 2021. These salmon are now found along major parts of Norway’s coast, but the situation is most serious in the east Finnmark region.

Áslat Holmberg grew up fishing salmon with nets. Like others in Finland's northernmost municipality, he has been coping with the impacts of a ban on salmon fishing intended to help stocks recover. He is also president of the Saami Council and a former member of the Saami parliament of Finland.