© Elisabeth Kruger / WWF-US

Can cooperation on fishing in the Central Arctic Ocean thrive as geopolitical conflicts persist?

The concept of cooperation is embedded in most international treaties. In keeping with this principle, the duty to cooperate in the conservation and management of living resources in the high seas is at the heart of the Law of the Sea and was fundamental to the negotiation of the Agreement to Prevent Unregulated High Seas Fisheries in the Central Arctic Ocean. As Nadia Bouffard explains, the process used to reach and implement this agreement is a great example of successful international cooperation—but ongoing commitments will be needed to continue it.

The collapse of high seas fish stocks—such as that of the pollock in the Aleutian Basin near Alaska—haunts fishers, communities and fisheries managers to this day. These collapses have usually followed intense fishing activity that took place before scientists could fully understand the risks or managers could impose regulations.

Recognizing the need for caution and conservation in the face of changing ice conditions in the Arctic—not to mention the risk that fishing fleets will eventually reach the area and cause history to be repeated—the five Arctic coastal states negotiated the legally binding Agreement to Prevent Unregulated High Seas Fisheries in the Central Arctic Ocean (known as the CAO Fisheries Agreement).

Cooperation and consensus

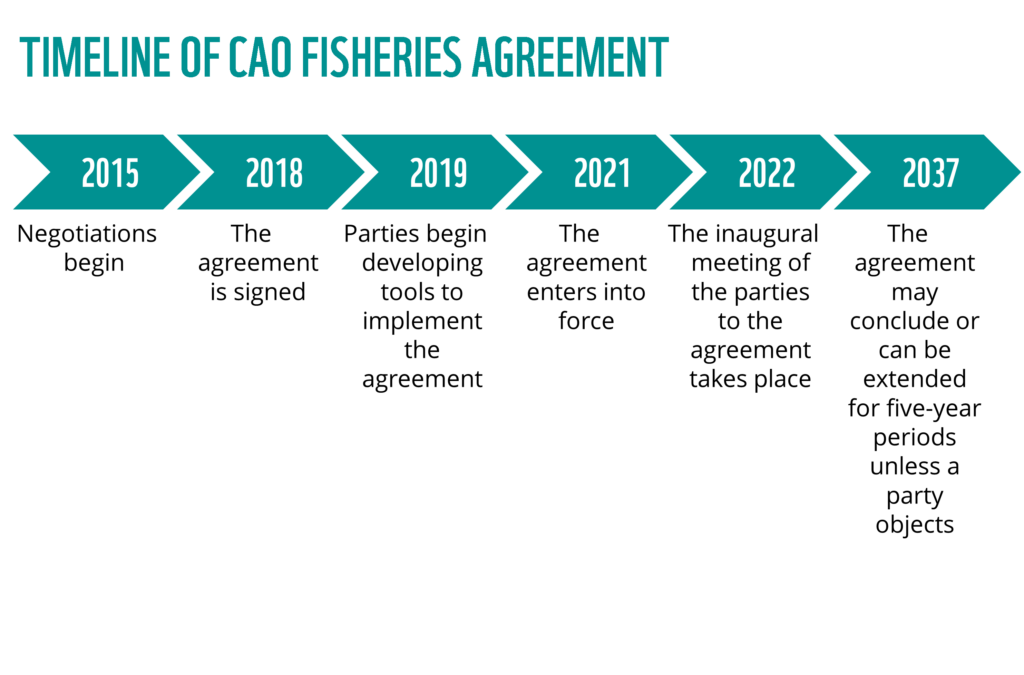

Canada, Denmark (Faroe Islands and Greenland), China, Iceland, Japan, Norway, Korea, Russia, the US and the European Union signed the landmark agreement in 2018. From the start of negotiations to the agreement’s entry into force following ratification by all signatories, the process is a testament to what can happen when countries are dedicated to working together for a common goal.

The agreement is meant to prevent unregulated fishing in the high seas area of the Central Arctic Ocean—an area roughly 2.8 million square kilometres in size—by establishing an interim prohibition on commercial fishing. This prohibition will remain until scientists can determine whether commercially viable fish stocks are present in the area and can be fished sustainably. In that event, the agreement also provides the basis for an orderly transition to a regulated fisheries management regime that would be negotiated by the parties.

Substantive decisions like this require the consensus of all parties.

Knowledge-based decision-making

An important focus of the agreement is the need to acquire data and knowledge to support fisheries management decisions. With a view to improving our understanding of the area’s marine ecosystems, the parties are required to establish a Joint Program of Scientific Research and Monitoring by June 2023. An innovative aspect of the agreement is the obligation to consider Indigenous and local knowledge in the development of the programme and to factor this knowledge into decision-making. The Inuit Circumpolar Council participated throughout the negotiation process and remains involved.

The agreement underscores the need for cooperation—not only among the countries involved, but with others, particularly Arctic Indigenous Peoples—to gather knowledge of the area and its resources, to better understand what impacts a fishery may have on fish stocks, other living resources and the ecosystem, and to establish regulatory measures before commercial fishing is authorized.

Implementation and ongoing dialogue

The countries that signed the agreement (nine countries plus the European Union) have been working together since 2019 to develop the tools needed to implement it. Fortunately, so far, the ongoing geopolitical conflicts have not prevented this work from moving forward. The inaugural meeting of the parties is scheduled to take place in November 2022 in Korea. A key objective will be to advance the work in order to meet the agreement’s timelines.

The CAO Fisheries Agreement breaks new ground by preventing unregulated fishing before it occurs. In doing so, it is the first of its kind. More groundwork is still needed to better understand how such fishing may threaten the fragile Arctic ecosystem and to provide for processes that support cooperation among the parties and others involved.

The agreement imposes a heavy burden to achieve consensus on substantive decisions—a feat that may prove challenging moving forward, particularly in the current geopolitical context. Continued dialogue and cooperation among the parties and with local Indigenous Peoples will be critical.

© WWF

By Nadia Bouffard

Chair, Conference of the Parties to the Agreement to Prevent Unregulated High Seas Fisheries in the Central Arctic Ocean

Nadia Bouffard chairs international fisheries and oceans bodies, including the Conference of the Par- ties to the Agreement to Prevent Unregulated High Seas Fisheries in the Central Arctic Ocean.