© Joshua Holko, Arctic Arts Project

News from the Arctic | Autumn 2022

MOSAiC study: Warm air mass found to carry “extreme” pollution from Eurasia to the Arctic

A recently published study is sounding alarm bells about a highly polluted warm air mass observed in the Arctic from 2019 to 2020. It found that the pollution concentration was significant enough to be concerning.

The Multidisciplinary drifting Observatory for the Study of Arctic Climate (MOSAiC) expedition was the largest-ever exploration of climate processes in the Central Arctic region. It aimed to gain a better understanding of the drivers of Arctic-accelerated climate change and how it is affecting the region.

The expedition saw an international team of scientists spend a year drifting in Arctic ice aboard the RV Polarstern. The collected data showed that a mass of warm air carrying pollutants from northern Eurasia had made its way into the high latitudes. The study is the first to reveal the chemical and microphysical properties of particulate matter swept into the Central Arctic by a warm intrusion.

Although it isn’t rare for warm air masses to reach the Arctic, the researchers were startled by the pollution concentration, which they said essentially “transformed the Arctic from a remote low-particle environment to an area comparable to a central-European urban setting.”

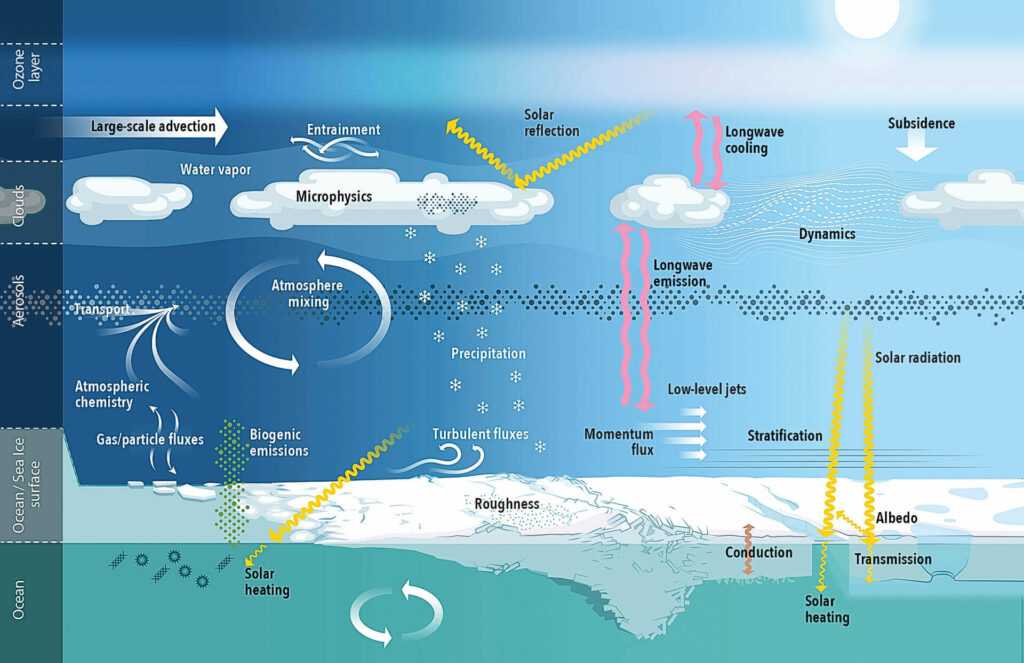

© From Shupe et al. Overview of the MOSAiC expedition: Atmosphere. Elementa: Science of the Anthropocene (2022) 10 (1): 00060. Reproduced with permission.

Build back better: Arctic research station reopens in Canada

The Canadian High Arctic Research Station, which had been open for only six months before the COVID-19 pandemic forced its closure, has reopened—and operators say the pause gave them an opportunity to make it even better.

Located in Cambridge Bay, Nunavut, the $250 million, state-of-the-art station was built to boost innovation in Arctic science and technology, welcome visitors and offer researchers accommodation and technical services. It supports research needs that range from ecosystem monitoring to DNA analysis. It opened in August 2019, then closed again early in 2020.

The unexpected closure ended up allowing staff to prepare for an influx of researchers returning to the Arctic and looking for connectivity. The station now offers a powerful public Wi-Fi network, a 3D printer and a mobile robot that can connect with people beyond Cambridge Bay, such as to get information about repairs or provide communications services.

During the long pause, researchers worked with the community of Cambridge Bay to help collect data while staff continued to fine-tune the new facility.

Evaluating approaches to scientific discovery: Remote collaboration supports breakthroughs

While many assume that face-to-face interaction is critical for generating new ideas, a recently published study out of the University of Oxford suggests that the rise of remote collaboration over the past few decades actually increased scientific discovery.

Researchers explored the link between the rise of remote collaboration and the increasingly incremental nature of scientific discovery—with, for context, the generally accepted idea that new ideas are becoming harder to find. They investigated how, against this backdrop, the rise of remote collaboration shaped the trajectory of science between 1961 and 2020.

They found that the negative effects of remote collaboration grew more muted over time, suggesting that the benefits of scientists being physically located in the same place declined as communications technology improved. Beginning in the 2010s, with the advent of video conferencing technologies, the negative impact tapers off and even becomes positive.

The authors caution that this doesn’t necessarily mean face-to-face interactions no longer matter. Digital meetings require planning, so spontaneous encounters are still important to scientific discovery. On balance, they found that local (in-person) and digital knowledge networks work best as complements to one another rather than substitutes.

Russia wildfire watch: Fire, destruction and toxic smog

It has been another difficult year for wildfires in Russia. The country’s Aerial Forest Protection Services published statistics in early August indicating that wildfires had burned at least 3.2 million hectares of forest in the country’s Siberian and Far East regions since the start of 2022.

Nearly half of the blazes were in the Khabarovsk region in the far east, though the west Siberian Khanty-Mansiisk autonomous district, across the country, was also severely affected. So far, the two regions have seen 2.14 per cent and 1 per cent of their territories burn, respectively. Fires blazing through villages in the Krasnoyark region in the east also killed at least eight people. A state of emergency was declared over the entire territory of Sakha, which has also been affected by toxic smog from the fires, including in residential areas.

Russia’s peak fire season typically begins in late May and lasts about 17 weeks. Last year, record-breaking wildfires in northeastern Russia consumed some 18.8 million hectares of forest. According to Global Forest Watch, fires were responsible for 69% of tree cover loss in Russia between 2001 and 2021. These wildfires are releasing millions of metric tons of carbon dioxide, contributing to the climate crisis.

By WWF Global Arctic Programme