©. Bo Eide, CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.com

In brief

News from the Arctic (2024.03)

Tracking methane pollution from space

MethaneSAT

Data from a privately funded satellite launched earlier this year could soon shed more light on the scale of methane pollution globally. MethaneSAT, a collaborative mission between Environmental Defense Fund, Google, the Government of New Zealand and several other partners, aims to identify and quantify the greenhouse gas.

Methane is about 80 times more harmful, in terms of causing climate change, than carbon dioxide for 20 years after its release into the atmosphere. Yet we don’t have a good understanding of its scale or precise origin points.

MethaneSAT’s mission is to detect and track methane from oil and gas production and consumption, the biggest sources of the polluting gas, as well as from coal mines, landfills and agriculture. It will use observed spectrographic data to calculate quantitative emission rates. This will reveal just how much methane is being emitted, where it is coming from, and how emissions change over time.

The satellite is expected to land later this year. The project team expects to be able to capture and attribute data on emissions from 80 per cent of oil and gas fields around the globe. The data MethaneSAT collects can then be used by oil and gas companies to quantify their emissions more accurately and improve their operations to reduce them. Governments and environmental agencies can also use the data to improve or enforce methane reduction regulations and track climate progress.

© Modified Copernicus Sentinel data [2019], processed by Pierre Markuse. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr,com

Sea ice loss drives boreal fires

WILDFIRE FUEL

Siberia has been a hot spot for summer boreal wildfires in recent decades, but the reasons for the rise have been unclear. A recent study suggests the culprit is declining summer sea ice in the Russian Arctic.

Summer sea ice reduction is the main cause of sea-ice loss on a long-term scale. The decline is fuelling two meteorological trends—vapour pressure deficits (VPDs) and Siberian blocking events—that, in turn, create the conditions for wildfires.

The study, published in Nature Communications, indicates that declining sea ice accounts for 79 per cent of the increase in the summer VPDs in the region through higher temperatures over land. A VPD is a measure of how much moisture the air can hold versus how much it is actually holding. In other words, it indicates the air’s drying power. A greater VPD can fuel wildfires by pulling moisture from plants and soils to make up for the deficit, making the vegetation more flammable.

Siberian blocking events are characterized by stalled high-pressure systems that cause prolonged periods of extreme weather that can fuel wildfires. Indirectly, these events are also driven by declining sea ice, which leads to warmer temperatures. They have been lasting longer and covering larger areas.

Mercury escaping into the environment

TOXIC METAL

As the Arctic warms, mercury that has been sequestered in permafrost for millennia is escaping into the environment, according to a study by researchers at the University of Southern California.

Mercury is a toxic metal that poses environmental and health threats. In the Arctic, it lurks in thawing riverbank sediment and can enter the environment because of erosion. Some three million people in the Arctic live in areas where permafrost is forecast to thaw completely by 2050.

The study’s co-author, Josh West, a professor of earth sciences and environmental studies at USC Dornsife, described the situation as a “giant mercury bomb in the Arctic waiting to explode.”

The research team analyzed mercury in riverbanks and sandbars, tapping into deeper soil layers. The levels they found were consistent with the higher estimates from previous studies, confirming that sediment samples provide a reliable measure of mercury content and offer deeper insight into the hidden dangers of thawing permafrost.

Three-year ICEBERG project studies Arctic Ocean pollution

MARINE POLLUTION

© ICEBERG project

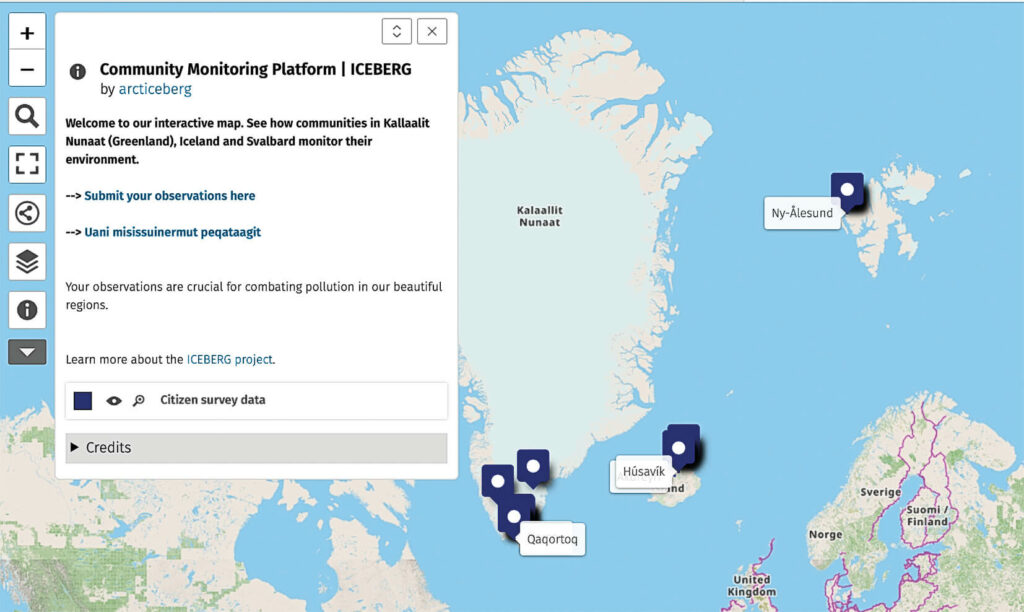

Over the next three years, researchers working on a project known as ICEBERG will study the impacts of ocean and coastal pollution on Arctic ecosystems and communities. The project is led by the University of Oulu (Finland) and involves researchers from 16 organizations and diverse fields, including toxicology, social science and environmental science. A key goal is to develop strategies to combat pollution and climate change and create policy recommendations to improve pollution control in the Arctic.

Field research will take place in three Arctic locations: western Svalbard, northern Iceland and southern Greenland. The sites were chosen because of their vulnerability to climate change and pollution and the economic importance of fisheries and tourism to their economies.

In Svalbard, research began in June 2024 and was slated to continue until October, with studies focusing on pollutants like marine litter, microplastics, chemicals and heavy metals. Additional research in Iceland and Greenland will emphasize community engagement, including collaboration with Indigenous and local populations.

Schools and interested citizens can collaborate in tracking pollution with drones. The project includes a mapping platform where citizens can add their observations.

By WWF Global Arctic Programme