© GRID-Arendal resources library / Peter Prokosch / CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

Can we turn off the tap on plastics?

Wading through the plastic problem in the Arctic Ocean

For more than 10 years, MELANIE BERGMANN has been studying plastics in the Arctic Ocean. It all started when the deep-sea scientist began looking at species on the Arctic Ocean’s floor and noticed a startling abundance of plastics and other human-made debris. This discovery kicked off her quest to find out where it was all coming from—and what impact it was having.

Since 2002, she and a team of researchers at the Hausgarten Ocean Observatory have been using a towed camera system to track debris on the deep-sea floor off the west coast of Svalbard—and what they’ve found is concerning. In just 13 years, the quantity of debris on the seabed has increased sevenfold—even 30-fold at the northernmost station. As she tells The Circle, plastic pollution is putting added stress on Arctic marine ecosystems, and it is time for the world to take concrete steps to stop it.

How big a problem are plastics and microplastics in the Arctic Ocean?

It’s like in the rest of the world—it’s ubiquitous. Everywhere we look, we find it. In some areas of the Arctic, the concentrations are as high as they are in less remote areas, and sometimes higher. For instance, the amount that we found on the sea floor was similar to that found in surveys done off the coast of Barcelona. This shows that there’s a real problem, especially when you think about how few people live in Svalbard compared to Barcelona.

© Deonie Allen

What kinds of plastic and other debris are you finding in these remote areas?

Much of it is just fragments, like bits of plastic film. It could be from plastic bags or fisheries. We also find bits of rope and glass. Glass is important because it sinks directly to the seafloor, indicating local disposal. Until 2013, it was legal to dispose of glass in the Arctic. It’s not anymore, but it can be hard to tell if the debris is old or new. On beaches, most of what we find is from fisheries.

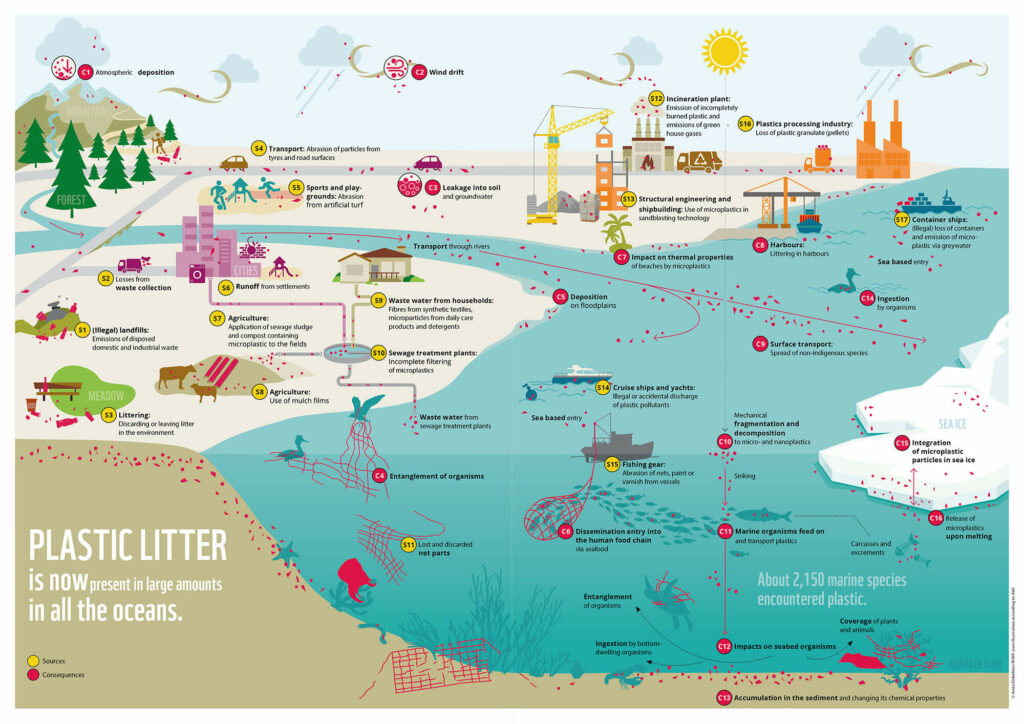

Do we know where all this litter is coming from?

We recently conducted a study where we asked citizen scientists in Svalbard to send us the litter they collected. We looked at every item to see if we could find a label or anything that would indicate where things were coming from. Only one per cent of the items showed signs of their provenance because most were from fisheries—and nets don’t have labels.

But 48 per cent of the items that did have labels originated from Russia and Norway, which are Arctic states. In fact, about 65 per cent came from European Arctic states, while another 30 per cent came from Europe, and the remaining five per cent came from very distant places like the US, Canada, Brazil and Argentina. Of course, some of it could have come from ships from those countries operating in the region.

So, can we ever really know where all this plastic in the Arctic is coming from?

I think the emerging consensus is that it’s coming from both local and faraway sources. As Arctic sea ice melts, we are seeing more and more human activity in the area, including hydrocarbon exploration, tourist cruises and shipping. The number of fishing vessels in the area has doubled and the number of cruise tourists has tripled. The number of ships calling at Svalbard increased tenfold between 2000 and 2014. I think the very presence of more ships in this part of the world means we will see even more plastics ending up in local waters, whether it is dumped intentionally or not.

And then there are airborne microplastics, which are carried to the Arctic by winds from various directions. We took snow samples on ice floes in Svalbard and found considerable concentrations. This is important because air moves much faster than water. Particles can travel thousands of kilometres in a matter of days.

How does all this plastic affect species, especially those in the Arctic Ocean?

This is something that we know little about. We do know that polar bears ingest and get entangled in plastic. I’ve seen bears with ropes around their necks, and plastic items have been found in their feces. About 91 per cent of northern fulmars (seabirds) in Svalbard have plastics in their stomachs, and it’s been found in other seabird species as well as in Greenland shark, which can live for 500 years.

We’ve also found it in zooplankton. That finding indicates that plastic has infiltrated the base of the food web. But to find out whether harm is being done, we would need to run experiments—and doing experiments with Arctic animals is not a trivial exercise. However, there is no reason why Arctic species should be less vulnerable to the effects of plastic than their relatives elsewhere. Quite the opposite, because they also have to deal with other severe changes as the climate heats. According to some recent studies, temperatures are rising four times faster in the Arctic compared to the global average.

I’ve seen bears with ropes around their necks, and plastic items have been found in their feces. About 91 per cent of northern fulmars (seabirds) in Svalbard have plastics in their stomachs, and it’s been found in other seabird species as well as in Greenland shark, which can live for 500 years.

If these plastics and microplastics are reaching such remote areas, what can be done?

We need to turn off the tap. I have big hopes for the UN Treaty on plastic pollution, which will be negotiated over the next two years. I hope it will contain measures to reduce the production of plastics in the first place. That decrease must be at the heart of any mitigation measures because we’ve seen eight per cent growth in plastic production annually, and already our systems in the developed world cannot cope. Still, countries can act before there’s a UN treaty in place. We don’t have to sit there and twiddle our thumbs.

What can be done in the Arctic region itself?

I think we have to reduce waste disposal from fishing boats. For instance, we could implement a one-fee system in the region: when ships come into port, instead of paying by the kilogram to dispose of waste, they would just pay a single fee no matter how much they bring. This would discourage them from dumping it at sea. Gear-marking schemes and education could also help.

And Arctic communities need better waste management systems. For example, in Greenland, Russia and a couple of other Arctic countries, there are open landfills on beaches in some areas. We should also improve sewage treatment in these areas, because even if there aren’t a lot of people living there, if everything goes into the ocean unfiltered, it adds up.

MELANIE BERGMANN is a senior scientist at the Alfred Wegener Institute Helmholtz Centre for Polar and Marine Research in Bremerhaven, Germany. She recently cowrote a report commissioned by the WWF on the impacts of plastic pollution on the world’s oceans.