© Alexander Mustard / WWF-UK

High Seas Treaty

Protecting biodiversity in the Arctic Ocean—now

The Arctic Ocean is undergoing unprecedented change as the climate warms, and there is much more to come. The international community—including Arctic states—must show leadership in protecting the Arctic Ocean’s biodiversity. ERIK J. MOLENAAR explains how the High Seas Treaty offers important opportunities to do so.

In 2023, the adoption of the High Seas Treaty was a sign of hope at a time of unparalleled ecological change in the Arctic Ocean. Despite growing geopolitical tensions, the international community was able to address the deteriorating status of marine biodiversity and ecosystems worldwide. Now, governments and stakeholders must take continued steps to bring the treaty into force and prepare for its implementation.

The High Seas Treaty—also known as the Biodiversity Beyond National Jurisdiction (BBNJ) Agreement—protects marine biodiversity in the high seas (the water column) and the international seabed. These two areas are known as “areas beyond national jurisdiction” because they lie outside the maritime zones where coastal states have authority, such as exclusive economic zones and continental shelves.

Four pockets, four approaches

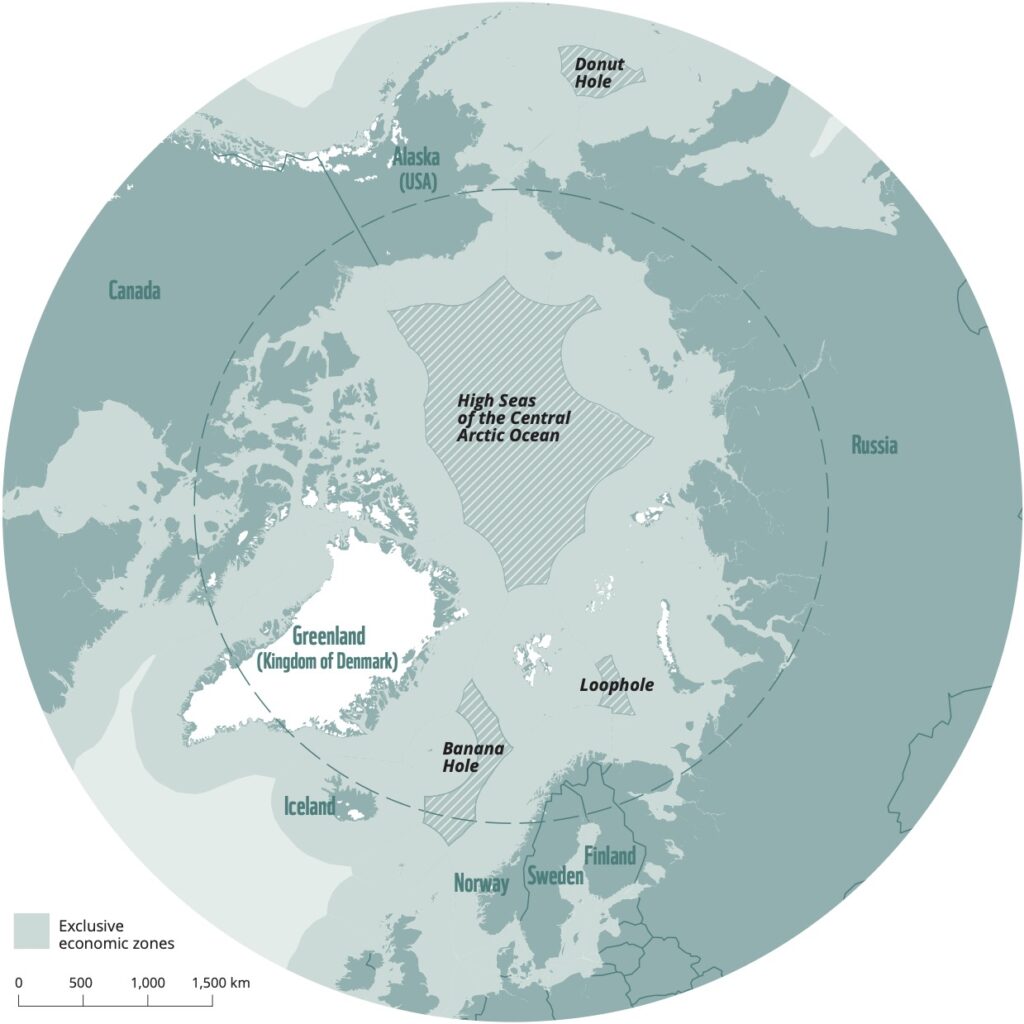

There are four pockets of high seas in the Arctic Ocean: the “Banana Hole” in the Norwegian Sea, the “Loophole” in the Barents Sea, the “Donut Hole” in the Bering Sea, and the high seas portion of the central Arctic Ocean (see map). There may also be a pocket of the international seabed beneath the high seas portion of the central Arctic Ocean.

The High Seas Treaty can be seen as a package deal on four topics: marine genetic resources, area-based management tools (including marine protected areas), environmental impact assessments, and capacity-building and marine technology transfer.

The treaty’s provisions on area-based management tools offer a concrete new mechanism to help achieve target 3 of the 2022 Kunming–Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework, which calls for 30 per cent of land and sea to be protected by 2030. But before this mechanism can be fully used, the treaty must enter into force. Currently, only 21 states have ratified it, and 39 more are needed.

Notably, none of the eight Arctic states have ratified the treaty so far.

The High Seas Treaty can be seen as a package deal on four topics: marine genetic resources, area-based management tools, environmental impact assessments, and capacity-building and marine technology transfer. So far, none of the eight Arctic states have ratified it.

There are four pockets of high seas in the Arctic Ocean: the “Banana Hole” in the Norwegian Sea, the “Loophole” in the Barents Sea, the “Donut Hole“ in the Bering Sea, and the high seas portion of the central Arctic Ocean. Map design: Ketill Berger, filmform.no. © WWF WWF Global Arctic Programme

Moving toward area-based management

Once the treaty is in force, any party to it will be able to propose area-based management tools in areas beyond national jurisdiction anywhere, including in the Arctic Ocean.

This means a proposal relating to the Arctic Ocean will not need to be submitted by an Arctic state—any treaty party would be able to do so. But to succeed, a proposal will need support from at least three-quarters of treaty parties. This will require significant engagement with all relevant states and stakeholders—not only Arctic coastal states and Arctic Indigenous Peoples, but also other “user” states, whose companies and vessels engage in activities in the high seas areas, as well as conservation organizations and industry associations.

At the heart of any area-based management tool are measures to restrict human activities, such as shipping or fishing. But before these measures can be adopted, the Conference of the Parties (COP) under the High Seas Treaty will often have to cooperate with existing international bodies that have a mandate to impose area-based restrictions on activities. Where such bodies exist, the COP cannot impose these restrictions on its own. It can only request that these bodies adopt them.

For example, in the high seas portion of the Central Arctic Ocean, the International Maritime Organization (IMO) has a mandate to adopt area-based restrictions on shipping, and two regional bodies—the Central Arctic Ocean Fisheries Agreement (CAOFA) and the North-East Atlantic Fisheries Commission—are empowered to adopt area-based restrictions on fishing. But so far, none of these bodies has exercised such powers in this high seas pocket. The situation in the other three high seas pockets is similar.

© Wojciech Strzelecki via commons.wikimedia.org, CC BY-SA 4.0

Steps to take now

This state of play reveals significant opportunities to make better use of the mandates that these global and regional bodies have to implement area-based protections in Arctic high seas. Initiatives to achieve this should be developed now rather than waiting for the treaty to formally take effect.

An example would be developing a concrete pilot proposal for a multi-sectoral area-based management tool in the high seas portion of the central Arctic Ocean. All the relevant stakeholder states and stakeholders mentioned above would need to be involved in such an initiative. While awaiting the treaty’s entry into force, the single-sectoral measures of the envisaged overarching (multi-sectoral) proposal could be submitted in a coordinated manner to all relevant global and regional bodies—including, in particular, the IMO and the CAOFA. Once these sectoral processes have led to a harmonized outcome, and the High Seas Treaty has entered into force, the overarching proposal with the sectoral measures could be submitted for adoption by the High Seas Treaty COP.

By actively engaging in these early efforts, Arctic states can demonstrate their leadership in marine conservation and responsible ocean governance and put the High Seas Treaty on a clear path to success.

By Erik J. Molenaar

Deputy Director, Netherlands Institute for the Law of the Sea, Utrecht University

LinkedInERIK J. MOLENAAR is Deputy Director at the Netherlands Institute for the Law of the Sea at Utrecht University.