© Richard Barrett / WWF-UK

A 50th anniversary

Recognizing five decades of collaboration

Polar bears have been intricately linked to Indigenous ways of life for millennia. Fifty years ago, countries that were home to polar bears agreed to work together to address the unregulated hunting of the bears by non-Indigenous people, which was considered to be having a negative impact on the species. But today, climate change is the major threat to polar bears’ future. The need for collaboration to address the challenges associated with the climate crisis is more pressing than ever. CAROLINE LADANOWSKI and DROPLAUG ÓLAFSDÓTTIR recount the major polar bear conservation steps that five governments have taken since 1973.

In the 1960s, there was international concern about polar bears because of unregulated hunting by non-Indigenous people. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) convened meetings with polar bear specialists to discuss the bears’ status and establish what is now known as the IUCN/Species Survival Commission for Polar Bears (or the Polar Bear Specialist Group). These meetings ultimately led to an agreement in 1973 to coordinate polar bear research activities and monitoring.

The 1973 Agreement on the Conservation of Polar Bears was signed by the bears’ five home states, also called the Range States: Canada, Denmark (Greenland), Norway, the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (now Russia), and the US. The agreement was ratified and went into force in May 1976 for an initial five-year period. In 1981, the Range States unanimously reaffirmed an indefinite continuation of the agreement.

Range States commit

The overall purpose of the 1973 agreement was to coordinate circumpolar efforts for polar bear management and the long-term preservation of the species and their habitat. The legally binding agreement prohibited the harvesting of polar bears except by Indigenous Peoples.

The Range States committed to coordinating actions relevant to the conservation and management of polar bears throughout the circumpolar range. They agreed to conduct national polar bear research programmes and to consult and exchange data from the studies. They also agreed to take appropriate steps to protect the ecosystem of which polar bears are a part.

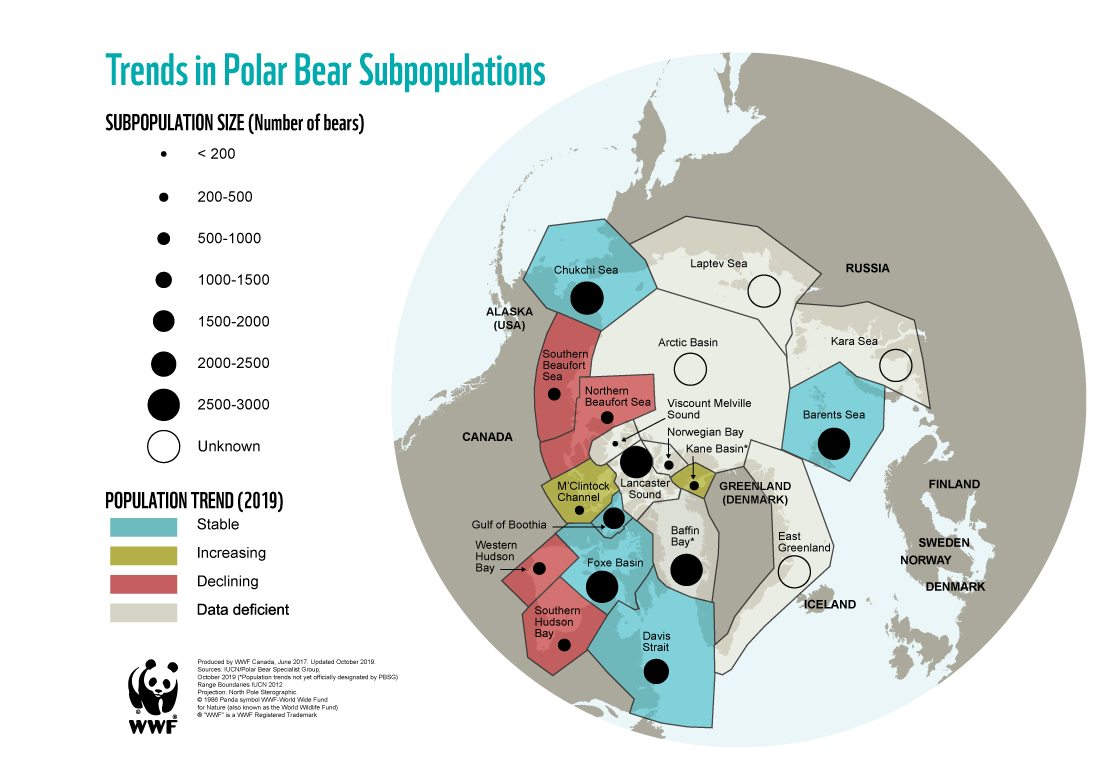

Since the ratification of the agreement, the threat pertaining to the over-harvest of polar bears has largely been eliminated. Norway and Russia have imposed a general ban on hunting, and the other countries manage it according to conservation acts and/or regulations. In Canada, home to more than two-thirds of the world’s total estimated polar bears, populations are co-managed in collaboration with provincial, territorial and federal governments, wildlife management boards, land claim organizations and Indigenous rightsholders. Canada has legislation that recognizes Indigenous rights and land claim agreements to ensure decisions include multiple knowledge systems and meaningful engagement with Indigenous Peoples for effective management.

Bilateral agreements are now established between Range States sharing responsibility for polar bear subpopulations to help ensure their good health and status and maintain sustainable harvests for Indigenous People. Protected areas have been established throughout the Arctic to safeguard essential polar bear habitat. All Range States have adopted national research plans for polar bears within their territories. At least one status assessment has been conducted for 15 out of 19 subpopulations in the last 31 years.

© naturepl.com / Jenny E. Ross / WWF

Climate crisis becomes key threat

In 1975, the polar bear was listed under the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) Appendix II. This means that stringent certification measures are required before polar bear products may be traded internationally. In 2015, the IUCN assessed the polar bear as Vulnerable.

Recognizing that continued international coordination is essential for the protection of polar bears, the responsible ministers of the Range States signed the 2013 Ministerial Declaration recommitting the states to develop a circumpolar conservation strategy. The declaration further recognizes climate change as the key threat to polar bears. It also acknowledges the importance of polar bears to Arctic Indigenous Peoples as well as the key role that Traditional Ecological Knowledge and the participation of Arctic Indigenous Peoples play in polar bear conservation.

In 2015, the Range States adopted a 10-year Circumpolar Action Plan to strengthen international efforts to conserve polar bears. The plan’s vision is to secure the long-term persistence of polar bears in the wild. It is supported by seven objectives and steps to meet them by 2025. The plan’s working groups and operating teams have successfully addressed actions that reflect its vision, such as publishing a climate change communications strategy to reach audiences beyond government, developing strategies to reduce human-polar bear conflict, and supporting sustainable trade action.

As climate change continues to have negative impacts on polar bears, international collaboration is essential even beyond Arctic regions. The Range States must also continue to apply responsible management practices and monitor polar bears while respecting relationships with Indigenous Peoples. In fact, although the continued cooperation of the five governments is critical, complete success depends on the participation of Arctic Indigenous Peoples. Their collaboration is as important as ever.

By Caroline Ladanowski and Droplaug Ólafadóttir

Scientists

CAROLINE LADANOWSKI is the Canadian head of delegation and current chair of the Polar Bear Range States Agreement. DROPLAUG ÓLAFSDÓT- TIR is a project officer supporting the Polar Bear Agreement with the Conservation of Arctic Flora and Fauna (CAFF) Secretariat.