© Clive Tesar / WWF

Industrial pollution

Steering away from scrubbers

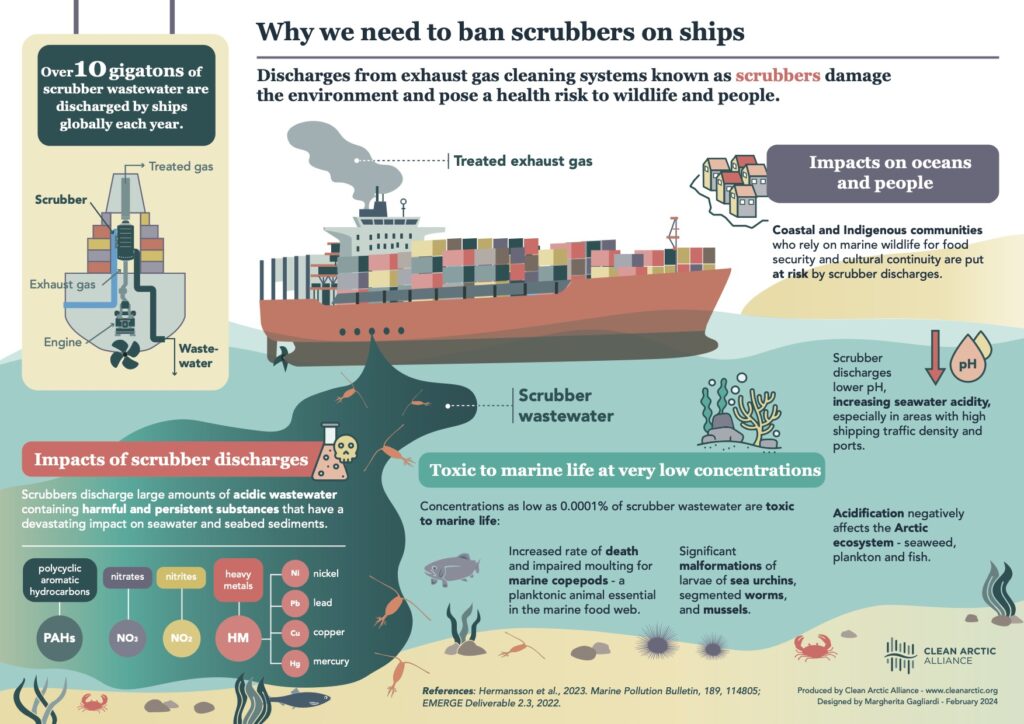

Scrubbers are exhaust gas cleaning systems that remove (or “scrub”) harmful pollutants and particulate matter from exhaust emissions before they are released into the atmosphere. Used in various industries since the Victorian era, the systems became more common in shipping in the 2000s to help ships comply with international emissions regulations, such as the International Maritime Organization’s 2020 sulphur cap. But as EELCO LEEMANS explains, we have better science now, and it’s telling us that wastewater from scrubbers harms marine life—so it’s time for a change.

“The solution to pollution is dilution”: that saying was frequently heard half a century ago, but since then, scientific knowledge on toxicology has proven it false. Pollutants can persist in the environment and bioaccumulate in the food chain. As a consequence, environmental policies and regulations now steer away from the dilution approach to protect life on Earth.

But some sectors—such as the maritime industry—appear to be stuck in the old narrative. While the shipping sector is quick to claim that shipping is the least environmentally damaging mode of transportation, have you ever encountered another transport mode whose vehicles deliberately dump millions of tonnes of pollution overboard?

That is exactly what the global shipping fleet does, day in and day out, even in the Arctic Ocean. Discharges of sewage and wastewater from bathrooms and kitchens, toxins from paints, cargo residues, lubricating oil, and wastewater from scrubbers all end up in the ocean, with detrimental impacts on marine life and the millions of people who depend on the ocean for their livelihoods and well-being.

Sending heavy metals and carcinogens overboard

In 2009, the International Maritime Organization (IMO) decided to regulate ships’ air emissions after calculating that pollution from shipping was contributing to more than 60,000 premature deaths each year. To reduce sulphur oxide (or SOx) emissions, ships can now choose from two options: they can reduce the sulphur content in the fuel they use, or they can install and use scrubbers.

Scrubbers remove SOx from exhaust by creating a mist of seawater in the ship’s smokestack that binds to the SOx. The resulting seawater with sulphur content is then flushed overboard. The low pH of this mixture contributes to the acidification of the oceans, which are already under stress from excess carbon dioxide (or CO2) uptake.

Compounding this problem, scrubbers pick up all kinds of other substances from the exhaust, including heavy metals, nitrites and nitrates, and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, which are highly carcinogenic. A genuinely toxic cocktail is routinely dumped overboard through ships’ discharge piping.

Scrubbers were deemed an acceptable solution by IMO members back in 2009. But 15 years later, a debate about this flawed approach is in full swing. Several recent studies have shown that scrubber wastewater cocktails have serious consequences for marine life. For example, even at a dilution of one part scrubber wastewater to one million parts clean seawater, an impact was seen on sea urchins, mussels and crustaceans, with lower fertilization rates and malformed larvae.

What this tells us is that the base of the marine food web is under threat.

The International Council on Clean Transportation has estimated that more than 10 gigatonnes of scrubber wastewater are pumped overboard into the world’s oceans every year. In response, more than 45 coastal and port states around the globe have raised concerns and started to regulate scrubber discharges in their coastal waters. The number of states on this list continues to grow: Denmark and Sweden plan to ban scrubber discharges in their territorial seas in 2025 because the Baltic ecosystem is suffering from multiple stressors.

A SHORT HISTORY OF SCRUBBERS

Although marine scrubbers only began to see widespread use by ships in the 2000s, the technology has been around since the 1850s, when the first basic scrubbers were introduced to remove pollutants from industrial exhaust, particularly in chemical plants.

Their use increased throughout the 20th century in industries like power generation, steel manufacturing and cement production as air quality regulations began to emerge, and became even more common in the 1970s in coal-fired power plants in response to concerns about acid rain.

The cleaner marine fuels available today contain much lower levels of sulphur than heavy fuel oil does, eliminating the need for scrubbers and their harmful side effects. It is time for the shipping industry to make the switch.

© Clean Arctic Alliance – www.cleanarctic.org

Who really picks up the tab?

Now, you might wonder what such decisions will mean for ship owners who have invested in scrubbers as an alternative to using cleaner fuel. It appears—again based on a scientific study published in Nature Sustainability—that more than 95 per cent of ships recoup the cost of the scrubbers they install within five years. This means the maritime industry will not suffer more than a minor loss if scrubbers are banned. Meanwhile, the marine ecotoxicity damage cost from scrubber water discharge in the Baltic Sea from 2014 to 2022 is estimated to be in excess of €680 million (USD$732 million).

It is time to say farewell to scrubbers, an outdated technology that is completely out of line with 21st century environmental standards for ocean protection. The best—ultimately, the only—solution is to ban scrubbers worldwide and require ships to switch to cleaner fuels as a step toward complete decarbonization.

In the meantime, scrubber wastewater restrictions should be rolled out as soon as possible, particularly in delicate ecosystems, such as Arctic waters. In January 2025, scrubbers will once again be on the IMO’s agenda when its Pollution Prevention and Response subcommittee convenes. Several environmental organizations will be present to push for the immediate and long-term actions needed to end marine pollution from scrubbers.

Sources:

https://helda.helsinki.fi/items/bb939453-8311-4e1e-88c7-4a3e8b9e80a3

https://emerge-h2020.eu/

https://theicct.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/Global-scrubber-discharges-fs-global-apr2021.pdf

https://theicct.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/Scrubbers_policy_update_final.pdf

https://www.researchsquare.com/article/rs-3534127/v1