© Doc White / naturepl.com / WWF

Taking stock

The future of Greenland’s narwhals

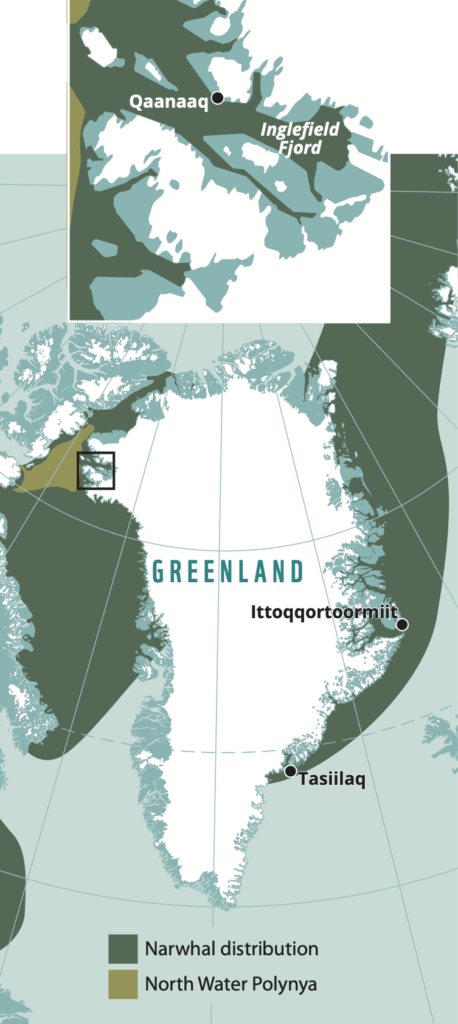

There are an estimated 110,000 narwhals in the world today. Found only in the Arctic—in the eastern Canadian Arctic, West and East Greenland, Svalbard, and the western Russian Arctic—these whales can live for more than 100 years and are highly specialized to live in the Arctic’s icy waters. As a result, they are considered more sensitive to climate change than any other Arctic marine mammal.

Depending on where they live, narwhals are affected by changing climate conditions, industrial development (such as shipping and oil and gas exploration and development), and Indigenous and traditional hunting. Shifts in their physical environments may include sea ice and water temperature changes as well as alterations in aspects of their biological environments, such as the type and quantity of prey and predators.

Illustration: Ketill Berger, ketill.berger@filmoform.no / © WWF Global Arctic Programme

© naturepl.com / Bryan and Cherry Alexander / WWF

Understanding how narwhals are doing

Narwhals inhabit both the east and west coasts of Greenland. While east and west don’t mix, some narwhals from West Greenland do swim across Baffin Bay to eastern Canada. This makes it complicated for researchers to track how populations are faring. But there are some key differences in the numbers and population trends of narwhals in different parts of Greenland.

According to scientific assessments, one West Greenland stock is possibly stable, although another is decreasing in number. Throughout Southeast Greenland, narwhal numbers are declining. In Northeast Greenland, where most of their habitat is protected by the world’s largest national park—a vast area of 1 million square kilometres—at least 2,000 narwhals are found.

All decisions about how narwhals in Greenland are managed are made by the Greenland government, or Naalakkersuisut. The government has a responsibility to conserve narwhals, including through international agreements on populations shared with Canada. The government makes decisions based on scientific advice, hunter knowledge, community consultations, and the goals outlined in international agreements. There is currently considerable debate among scientists, scientific committees, hunters, conservationists and managers about how the decisions the Greenland government is making about narwhal population management will affect their future.

© Staffan Widstrand / WWF

Hunters’ observations of narwhals in Northwest Greenland

Narwhals have always been culturally significant to Greenlandic people. Every summer in Northwest Greenland, large pods of narwhals arrive and spend the warmest months in Inglefield Bredning (Fjord). Inuit hunters from Qaanaaq, a community located at the northern entrance of the fjord, harvest them for their tusks, meat and skin. The animals provide a critical source of food in remote communities.

In recent years, many hunters have witnessed changes in the narwhals that spend their summers along the coast of Northwest Greenland. Qumagaapik Kvist is one of them. In the decade since the young hunter from Qaanaaq started harvesting narwhals, he’s noticed changes in both their physical condition and number. He and other hunters from the area say that narwhal numbers are increasing, but the animals are much thinner than in the past.

“Many have little fat or blubber because they don’t have enough to eat,” says Kvist. “I hear that, and I can also see it.”

Management of narwhal hunting in West Greenland came under a quota system in 2004 after international concern about declining stocks and scientific findings that harvest levels were not sustainable. But hunters in the region question whether the quotas reflect what they are witnessing firsthand. They argue that quotas aren’t needed if traditional hunting methods are used.

“Our tradition is kayak and harpoon,” says Rasmus Daorana, a resident of Qaanaaq and hunter for many years. “We can’t hunt when the sea is frozen or when the wind blows. Nature is our boss, and it gives us limits. This means a quota is not necessary.”

Daorana also says that local rules for narwhal hunting were in place before the quotas came in. “There were areas where you could only row your boat without using a motor, and hunters were not allowed to wait [for the narwhals] in their boats—most of us waited on land. Now all of that is gone.”

Adolf Simigaq, who’s been a hunter in Northwest Greenland for more than 20 years, believes quotas are the reason hunters are seeing thinner narwhals.

“When there are too many narwhals, there is not enough food for all of them,” he says. “It is dangerous that the government is making the quotas smaller.”

Once they leave Inglefield Bredning at the end of summer, narwhals migrate to the North Water Polynya, or Pikialasorsuaq, for winter. Straddling Canadian and Greenlandic waters, it is the Arctic’s largest polynya and one of its most biologically productive places. Narwhals that spend summers in the Canadian high Arctic also use the polynya. Some of the Qaanaaq hunters suspect there is another reason why they might be seeing more narwhals in Northwest Greenland.

“Canadian narwhals are coming from the polynya and mixing with ours,” says Kvist. Daorana notes the same, and describes them as having a different body colour and length as well as different behaviours from the narwhal in their local stock.

The Qaanaaq hunters note other changes, too. Kvist says less sea ice and warmer temperatures are attracting more cruise ships and larger boats to the fjord where he lives. This is scaring off the narwhals, which are extremely sensitive to underwater noise—an observation that has been made both by hunters and scientists.

And it isn’t just ships that are appearing. Orcas are starting to arrive every year, causing the narwhals to move into the shallower waters of the fjord, where they are easier to catch.

“That’s good for hunters,” says Kvist. “But the orcas are catching more narwhals than I am. And sometimes they just kill without eating.”

© Nansen Weber

Scientific advice on narwhals in Southeast Greenland

On the other side of this vast country live the Southeast Greenland narwhals. Recent counts, including from a 2022 survey planned and executed by scientists and hunters together, indicate that the situation for narwhals in this area is dire.

“We have a population that has declined from more than 1,700 to only a few hundred since 1960,” explains Mads Peter Heide-Jørgensen, a professor at the Greenland Institute of Natural Resources and a member of the Northern Atlantic Marine Mammal Commission’s (NAMMCO) working group on narwhals in East Greenland. “In one area of Southeast Greenland, we weren’t able to detect any animals at all during the past two aerial surveys. They’re at high risk if hunting continues at any level.”

Narwhals in Southeast Greenland do not venture outside Greenlandic waters and are the sole responsibility of the government to manage. They are hunted by residents of two communities—Ittoqqortoormiit and Tasiilaq—under a quota system set by the government.

Scientists like Heide-Jørgensen point to dwindling numbers in this area as a clear alarm bell that more regulation is needed. For the past several years, NAMMCO has recommended a moratorium on narwhal hunting in the three Southeast Greenland management units. But the Greenland government has resisted the call to implement a zero hunting quota, saying that hunters’ knowledge of the number of narwhals differs from the science. It argues that a ban on hunting will threaten food security and prevent traditional hunting techniques and culture from being passed down in Indigenous communities.

The Greenland government has resisted the call to implement a zero hunting quota, saying that hunters’ knowledge of the number of narwhals differs from the science.

It might also come down to economics. For many Greenlandic communities, selling narwhal products is economically important. The government banned the export of narwhal tusks in 2006 because unsustainable hunting levels meant trade could have a detrimental impact on narwhals. But there’s a thriving commercial domestic trade in narwhal skin, known as mattak. The high prices paid for mattak create a strong incentive to continue narwhal hunting. But it’s also part of local peoples’ cultural identity, considered a healthy “soul” food that provides important vitamins. Mattak is a delicacy served at special occasions, such as weddings, baptisms, communions and other festivities.

Undoubtedly, narwhals face a range of pressures, especially in Southeast Greenland, where sea temperatures are rising, sea ice is retreating, and ship traffic is on the rise. But a concern shared by many scientists, including Heide-Jørgensen, is that continuing to remove narwhals from this tiny population through hunting will have a much more immediate and permanent impact.

“In Southeast Greenland, a [hunting] ban is the only way to protect the stock if you want to have narwhals in the future,” he says.

Finding ways to conserve narwhal populations for future generations while meeting the needs of Greenlanders today is a complex task facing Greenland’s government, and it will entail bringing together multiple knowledge systems to inform decisions. But maintaining abundant populations of narwhals throughout Greenland is essential for a healthy, balanced ecosystem, healthy people and lasting cultural identity—something everyone can agree on.

By WWF Global Arctic Programme