© Matthias Fuchs

Permafrost

The hidden glue holding northern landscapes together

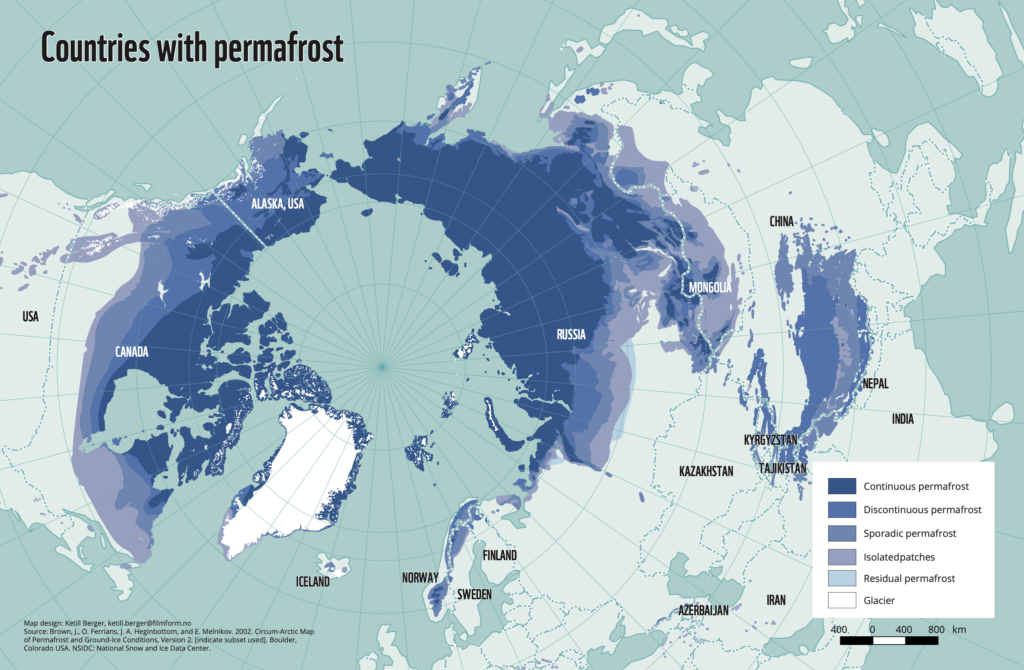

Permafrost is found under vast areas of tundra and boreal forest in the Arctic regions of Alaska, Canada, Scandinavia, Finland and Russia. But as CLAIRE TREAT explains, it is warming and thawing everywhere, with consequences not only for local people and wildlife, but for us all.

Permafrost is the word for frozen ground in cold regions where temperatures remain below freezing for much of the year. But the word itself is becoming something of a misnomer as permafrost becomes less permanent in response to climate warming, which is occurring far more quickly and having more extreme consequences in the polar regions.

When temperatures rise, permafrost can thaw, causing dramatic changes to the landscape that can have significant consequences for people and wildlife. For example, new lakes can form while others dry up. Thermokarst landscapes can emerge as ground surfaces collapse, creating uneven terrain. When ground ice thaws on slopes, thaw slumps (a type of landslide) can occur as soil, debris and vegetation shift.

Thawing permafrost has the most direct effects on the people and wildlife living in Arctic regions. Coastal areas in these regions see shorelines disappear while coastal communities lose houses and land. Roads, buildings and other infrastructure built on permafrost can begin to fail and need repair or stabilizing. Wildlife like caribou and reindeer count on solid permafrost to move across what would otherwise be wetlands. Palsas (peat mounds with permanently frozen peat and mineral soil cores) have long been ideal spring foraging habitats for reindeer in Finland, Sweden and Norway, but are disappearing.

These are just some of the effects on local people and wildlife that we already know about. There are likely more that we haven’t identified yet.

© Jens Strauss, Alfred Wegener Institute

Decomposition will accelerate the climate crisis

The impacts for those of us not living on permafrost may be less immediate, but they will be no less dramatic. Permafrost regions are key carbon reservoirs. When the ground stays frozen, the permafrost acts as a freezer (or even a glue) for the vast amounts of carbon found in soil that have built up over time. Plant litter, roots and other organic materials in the soil are preserved when they stay frozen. With warming, they will begin to defrost and decompose, releasing carbon into the atmosphere and accelerating climate warming. The permafrost regions in the northern hemisphere store about twice as much carbon as is currently found in the atmosphere.’

We still don’t have a good understanding of how much carbon is being released due to permafrost thaw. This is partly because the Arctic is so remote and difficult to access. We have limited measurements of carbon exchange across the vast permafrost region, especially in Russia. There are a number of sites in Alaska, Finland and Sweden that provide important information, but their limited numbers make trends in carbon uptake and release difficult to detect. Based on our best knowledge, we surmise that carbon emissions due to permafrost thaw will be equivalent to emissions from a mid-sized country by the end of the century under a moderate warming scenario of 2 to 3°C.

But we aren’t certain. As scientists, we need to figure out how to improve our measurement network and our predictions to answer this key question.

© Torben Windirsch-Woiwode

Possible solutions

While the effects of climate warming on permafrost are concerning, there are some glimmers of hope from both the human and natural sides. As scientists, we continue to develop new technologies—such as satellites, drones, and new autonomous devices—to measure carbon emissions in remote regions. These are critical to our ability to understand and monitor what is happening.

In addition, nature may help sequester carbon in some areas. For example, flooding associated with permafrost thaw can result in the formation of new wetlands with high rates of carbon uptake. Or warmer temperatures and higher atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations may enhance plant growth, increasing natural carbon sequestration. Both of these developments could offset a certain amount of carbon losses from thawing permafrost.

Still, the best path to keeping permafrost carbon in the ground is to limit emissions from fossil fuels and deforestation. This way, we can minimize temperature increases and ensure Arctic and boreal soils stay frozen. This can help us to preserve these beautiful and sensitive landscapes and protect those who live on them for the future.

Let’s keep permafrost frozen so it can continue to hold ancient carbon sources in place and provide a solid base for the people and wildlife living on its surface.

By Claire Treat

Senior researcher, Alfred Wegener Institute

CLAIRE TREAT is a senior researcher specializing in permafrost carbon and greenhouse gas emissions research at the Alfred Wegener Institute Helmholtz Centre for Polar and Marine Research.