The march of the beaver into the Arctic

Species moving north

The Arctic has long been home to species that are well-adapted to the region’s cold, harsh conditions—from polar bears and caribou to narwhals and ringed seals. But now these species have a new neighbour: the beaver. And its appearance in Alaska could have significant consequences for ecosystems and biodiversity.

KEN TAPE is an associate professor at the University of Alaska Fairbanks who has spent much of the last five years photographing and studying beavers in western Alaska. He and several other scientists have used time series of satellite images to document the appearance of hundreds of new beaver ponds in tundra regions of western and northern Alaska. He spoke to The Circle about the beaver’s expansion into the Arctic and what it could mean for tundra ecosystems.

How much has the beavers’ range expanded in recent years?

In Alaska, beavers started moving into tundra regions 40 or 50 years ago and have continued to move outward. At this point, they’re all the way out at the west coast of Alaska. They’ve actually made it out to the Bering Strait, which is kind of impressive. So far, we’ve mapped about 12,000 or 13,000 beaver ponds in the Arctic tundra of western Alaska.

How were you able to track this movement?

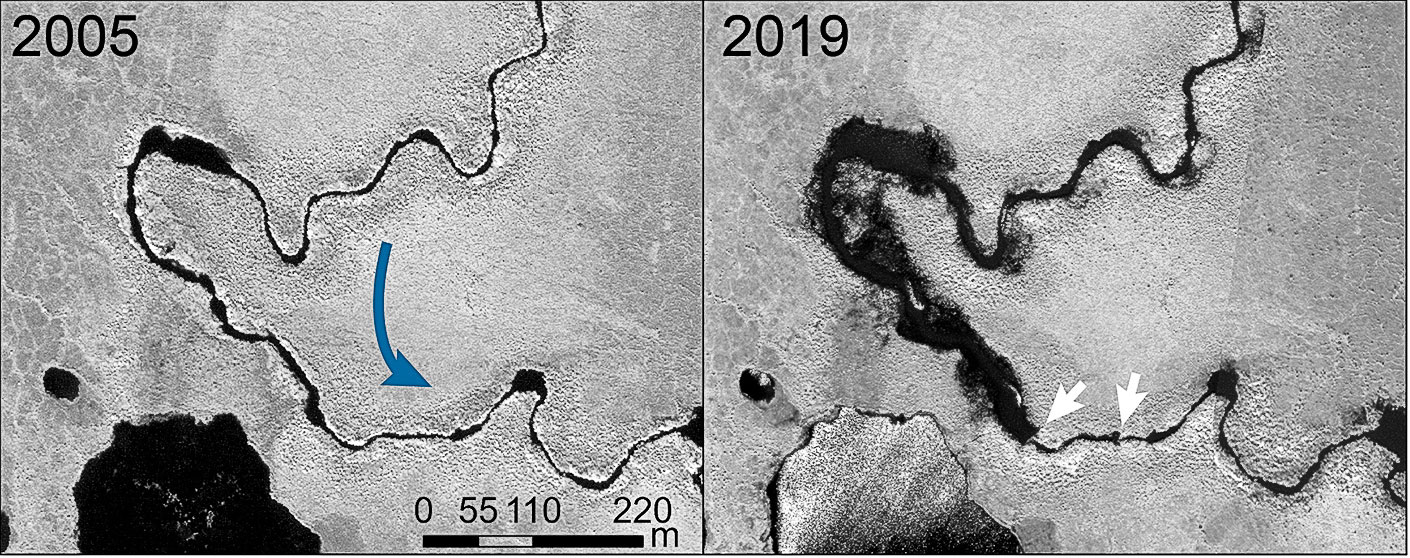

What’s interesting about beavers is that, like people, they make a mark on the landscape that you can see from space. That’s what makes this exciting and such an interesting project. It’s not just about a species responding to climate change—it’s a species imposing changes on the landscape. That’s how we are able to say when they got there. You can go back and look at old aerial photography and see beaver ponds being built along streams.

© Ken Tape

Where was the beavers’ range 40 or 50 years ago?

I would say they were restricted to the boreal forest. Remote tundra communities of Alaska really have no record of beavers ever having been there. But hunters have trapped beavers heavily across the northern hemisphere, so part of what we’re seeing is a natural rebound. For example, in the woods around Fairbanks, there probably weren’t many beavers 150 years ago. But because the records don’t go back to before the fur trade, we don’t know if beavers were ever out there. And that’s an important question.

Why have they started to move into the Arctic?

There are two key reasons, but we don’t know which is playing the biggest role.

One is climate change. This is an animal that needs shrubs and saplings, and we know that shrubs are expanding in the Arctic and that the amount of open water in winter is also increasing. That’s important because beavers don’t hibernate.

So it’s obvious that their habitat has increased in the Arctic due to climate change. But at the same time, they are rebounding from being over-trapped in the 18th and 19th centuries. That’s why this question of “Where were the beavers before the fur trade?” is so important. Were they out at the Bering Strait in 1700? We don’t know. We’re working with archaeologists to look at beaver teeth and bones to try to find out.

From a biodiversity standpoint, what are the consequences of this movement of beavers?

Our hypothesis is that beaver ponds are like oases in the tundra. When you pool water on a permafrost landscape, you begin to thaw the permafrost around and underneath the pond. And that’s a key idea because in more southern ecosystems, people use beavers to trap groundwater in order to widen floodplains and restore dried-up streams to bring fish back. That’s what beavers do when they get into a temperate ecosystem.

Beaver dams in the Arctic do all those things too, but they also essentially create heat islands, or oases, because they trap the water on the landscape and the water then traps heat, so the ice doesn’t freeze all the way down at the bottom in winter. The result is deeper, warmer water that thaws the permafrost. Our hypothesis is that this will increase biodiversity because it allows boreal forest species to get a foothold in the Arctic. But that’s just a hypothesis for now.

© Imagery 2021 Maxar

Is there a negative impact of this expansion?

Well, I think a lot of people would say that thawing permafrost is a negative impact. That’s the big one. We also have preliminary evidence of methane hotspots surrounding beaver ponds. These can create a completely different ecosystem. In the Arctic, there are all these little streams. Then suddenly a beaver moves in, and the streams and landscape never look the same again. This could increase biodiversity, but the endemic species might get squeezed out. For example, you could get fish species like salmon moving northward. Some endemic Arctic species will probably get outcompeted, but that’s just guesswork right now.

Could what you discover lead to decisions about management?

That’s a difficult question. For one thing, I’m not sure how easy it is to stop what’s happening. You can already harvest as many beavers as you want in Alaska, yet I think that’s probably barely making a dent in their expansion. We have formed a group called the Arctic Beaver Observation Network. The idea is to synthesize research and put the findings into the hands of land managers and local people so they can make informed decisions. But what they can actually do to stop it, I’m not really sure.

© Ken Tape

By WWF Global Arctic Programme