Photo credit: © Terry Milton / Government of Nunavut

Sea ice signals

Using artificial intelligence to keep caribou ice highways clear

Every autumn, the Dolphin and Union caribou herd undertake a perilous sea ice crossing from Victoria Island in the Canadian Arctic to the mainland coast of Nunavut and the Northwest Territories in search of better winter foraging. But the impacts of climate change and mounting icebreaker traffic in the area are threatening this vital route. ELLEN BOWLER and LISA-MARIE LECLERC explain how sea ice forecasts that use artificial intelligence (AI) could help predict caribou crossing times and inform proactive conservation.

It’s already the start of the fall migration season in the north, and the Dolphin and Union caribou herd is gathering on the south coast of Victoria Island. The caribou are waiting for a stable platform of sea ice to form a bridge that will allow them to journey south to their mainland winter pastures: connectivity between the caribous’ summering and wintering ranges is critical to their ability to thrive and reproduce. But a warming climate and transiting icebreaking vessels—which create open water leads—can delay the formation of these essential ice highways.

On the frontlines of this issue, local teams and Indigenous communities are developing solutions to manage the pressures on caribou and people that use the same ice highways. Vessel awareness is also a top priority during the open-water season, given that large ships pose serious risks to everyone navigating the changing Arctic seascape. Communication between multiple groups, including Hunters and Trappers Organizations, governments and vessel operators, is crucial.

A few initiatives have already been launched—for example, a Notice to Mariners system now recommends that ship captains communicate with community contacts during caribou migration times to find out about the risks. The system also recommends that ships adopt safe transit speeds to avoid disrupting the migration.

Barren-ground caribou, © Peter Ewins / WWF-Canada

Dealing with unpredictability

But a major challenge remains: the timing of the caribou’s crossing is highly variable. Caribou are known to begin crossing as soon as the sea ice is stable, but that timing varies annually. As a result, advisories must cover wide time frames and may not precisely reflect the actual migration timing in any specific year. These advisories could prove even more insufficient as the climate continues to change.

We need to know with greater certainty when the ice will form each year. But sea ice forecasting is a notoriously difficult task that traditional physics-based models have struggled with. The models often fail to produce predictions at an accuracy or resolution that is relevant for people in the Arctic, despite requiring huge computing resources and large teams to deploy.

IceNet trains its models on decades of satellite observations. By learning from this vast historical dataset, the model can understand how sea ice develops in response to a wide range of atmospheric and ocean variables.

This is where IceNet, a cutting-edge sea ice forecasting initiative based on AI and led by the British Antarctic Survey and Alan Turing Institute, can help. IceNet trains its models on decades of satellite observations. By learning from this vast historical dataset, the model can understand how sea ice develops in response to a wide range of atmospheric and ocean variables. It has not only proved to be more accurate than leading physics-based models, but also produces forecasts in seconds on a normal laptop—a game-changer for time-sensitive decision-making.

AI meets local knowledge

To create a tool for caribou conservation, we combined IceNet’s forecasting abilities with local expertise. For decades, the Government of Nunavut has conducted extensive research on the Dolphin and Union caribou using GPS collars, building up a wealth of telemetry data. By fusing these data with satellite observations of sea ice, we were able to build a deeper understanding of how migration timing relates to ice formation.

Now, instead of just forecasting sea ice, we can use IceNet to predict when the caribou are most likely to begin migrating. The software tools allow experts to review forecasts and migration predictions and integrate the information into other knowledge and data streams. These early-warning alerts and tools could lead to more finely tuned conservation measures, such as by refining estimates of when icebreakers should avoid an area or giving ship operators advance notice so they can adjust their plans, ensuring safe passage for caribou.

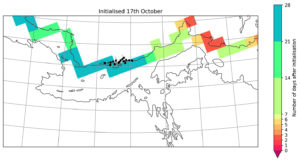

An example of an IceNet early-warning map, generated with a start date of October 17, 2022, predicted how long it would take from that date for the sea ice to start reaching a safe crossing level for caribou. In this example, even though the herds were already gathered at the coast, IceNet predicted that it would be two or three weeks before safe ice formed.

For people who live in the Arctic, where culture is deeply intertwined with caribou, developing problem-solving tools that can inform strong conservation measures alongside future economic development will be vital as the climate continues to change. This AI-based framework could play a part in the future of conservation and management in the region. For example, beyond its uses to protect the Dolphin and Union caribou, the technology could be adapted to predict when polar bears are likely to come ashore near communities and alert residents of potential conflicts. It could also be tapped into to help protect whale migration corridors and safeguard large walrus haul-out sites from increasing human pressures.

In the face of rapid climate change, combining local expertise with innovative technology is crucial to building adaptive measures. By developing tools like IceNet in collaboration with people who live and work in the Arctic, we can build solutions for people and wildlife as they adapt to a swiftly changing ice world.

To create a tool for caribou conservation, we combined IceNet’s forecasting abilities with local expertise. For decades, the Government of Nunavut has conducted extensive research on the Dolphin and Union caribou using GPS collars, building up a wealth of telemetry data. By fusing these data with satellite observations of sea ice, we were able to build a deeper understanding of how migration timing relates to ice formation.

Now, instead of just forecasting sea ice, we can use IceNet to predict when the caribou are most likely to begin migrating. The software tools allow experts to review forecasts and migration predictions and integrate the information into other knowledge and data streams. These early-warning alerts and tools could lead to more finely tuned conservation measures, such as by refining estimates of when icebreakers should avoid an area or giving ship operators advance notice so they can adjust their plans, ensuring safe passage for caribou.

For people who live in the Arctic, where culture is deeply intertwined with caribou, developing problem-solving tools that can inform strong conservation measures alongside future economic development will be vital as the climate continues to change. This AI-based framework could play a part in the future of conservation and management in the region. For example, beyond its uses to protect the Dolphin and Union caribou, the technology could be adapted to predict when polar bears are likely to come ashore near communities and alert residents of potential conflicts. It could also be tapped into to help protect whale migration corridors and safeguard large walrus haul-out sites from increasing human pressures.

In the face of rapid climate change, combining local expertise with innovative technology is crucial to building adaptive measures. By developing tools like IceNet in collaboration with people who live and work in the Arctic, we can build solutions for people and wildlife as they adapt to a swiftly changing ice world.

Ellen Bowler is a machine learning researcher with the British Antarctic Survey’s AI Lab.

By Lisa-Marie Leclerc

Regional Biologist, Kitikmeot region, Nunavut

Lisa-Marie Leclerc is a regional biologist for the Kitikmeot region of Nunavut.