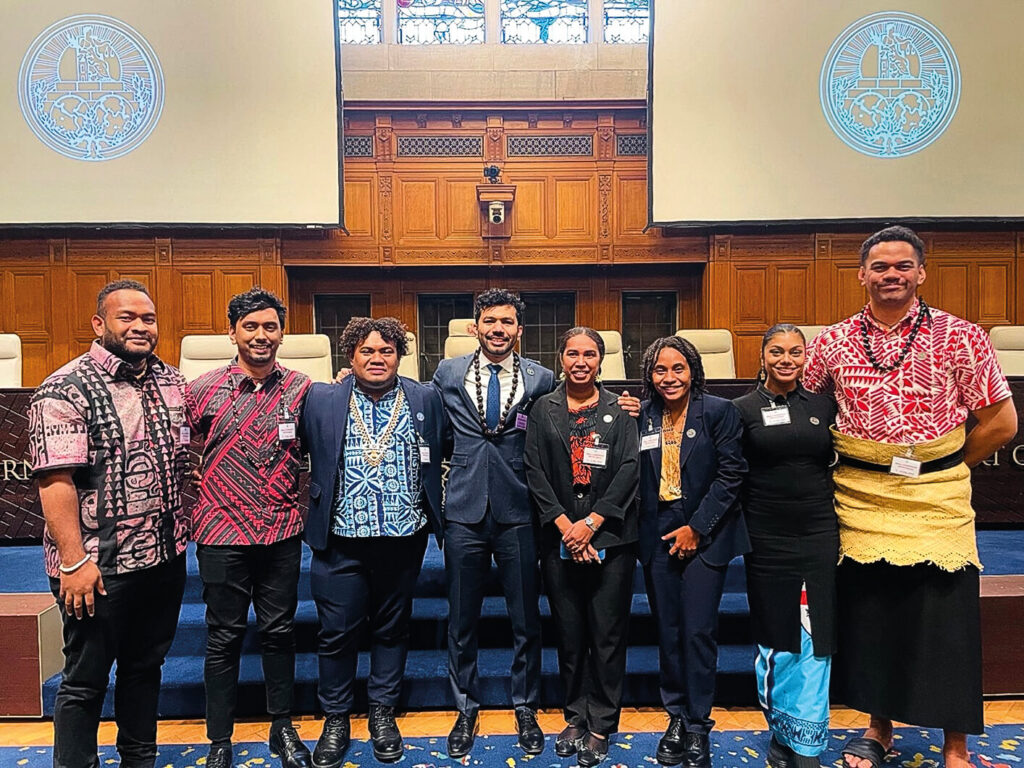

© Cynthia Houniuhi

International Court of Justice

Using the law to hold high-emitting states to account

Like the Arctic, the Pacific Islands are on the frontlines of the climate crisis. Accelerating sea level rise and ocean warming and acidification threaten the existence of these islands and the people who call them home.

In 2019, a group of 27 law students at the University of the South Pacific decided it was time high-emitting states paid for the unprecedented environmental changes they were causing. The students formed a group called Pacific Islands Students Fighting Climate Change and started a campaign to persuade the leaders of the Pacific Island Forum to take the issue of climate change and human rights to the International Court of Justice.

The campaign worked. In December 2024, the group’s president, CYNTHIA HOUNIUHI, delivered a powerful statement to the court calling for climate justice and the recognition of the principle of intergenerational equity. The case could have ramifications not just for people in the Pacific Islands, but for those in Arctic communities. Houniuhi spoke to The Circle about the urgent need to rein in the climate crisis and hold polluters accountable.

What are the effects of climate change where you live?

My father is from South Malaita Island, in the Solomons, and there’s an island nearby called Fanalei. Over the course of just a few years, you could just see how the sea had sort of eaten the island, and how the houses were literally standing in the sea. So, the most obvious impact is sea level rise. People have moved because they weren’t able to live there anymore. It looks abandoned now, at the brink of being completely engulfed by salt water. But when I was growing up, it used to be this beautiful island where children could be seen playing on the beach.

Also, you can speak to fishermen, and they will tell you that the weather is becoming unpredictable. They can’t depend on their traditional knowledge anymore—knowledge that was built from interacting with nature in their everyday lives. When they go fishing, based on this knowledge, they anticipate that it will be good because the wind is blowing in a certain direction. However, once they’re out at sea, the wind blows from an unexpected direction. Sometimes they get lost at sea because they find themselves in the middle of a storm they weren’t prepared for.

© N Photo/ICJ-CIJ/Frank van Beek. Courtesy of the ICJ. All rights reserved.

How did the idea come about to take the issue of climate change to the International Court of Justice?

It started in our international environmental law course at the University of the South Pacific. All 27 law students in the class were from frontline communities—those that don’t have the luxury of seeing climate change in an abstract way. When they think of climate change and sea level rise, they have clear pictures in their heads.

For me, it was my father’s island. Seeing how it changed over a short period of time really pushed me to act. When I went to university, I started learning about climate change and the existing climate regimes, and the more I learned, the more it became not just about climate change, but about climate justice. Because you see the effects of it. You see your people being forced to move, and you know what caused it. And you ask yourself why you are carrying this burden when your country contributes almost nothing to cause this.

It became a personal journey for me. That’s why I stuck with it for five years on a voluntary basis. The journey for me has always been about my people and how we can better protect ourselves, especially future generations. Finding allies along the way, those from frontline communities and those that believe in this cause, has helped realize this goal.

Why did your class decide to take this case to the International Court of Justice?

As law students, we wanted to see how we could use the law to help our people. And our lecturer, Dr. Justin Rose, challenged us to go beyond the four walls of the classroom. The more we learned about climate regimes, the more we were struck by how slow the progress has been in terms of solutions compared to the impacts of climate change on our people. As young people in that law class, we were worried about what we could do to protect our children and their children. We wanted to bring human rights into the discussion. We wanted greater protection for the principle of intergenerational equity, the idea of one generation being fair to the next. At the moment, future generations are not being considered in the context of climate change.

Additionally, there is something special about the Pacific region. There is a unique collaboration between states and civil society organizations that is found nowhere else. It is a basic understanding that the issue of climate change is more than carbon markets, harmful industries and monetary gains and losses—it is literally a life-or-death fight against an assault on our human rights.

What are you and your former classmates hoping to achieve by taking this case to the International Court of Justice?

We want an outcome that will reflect the reality of what we are seeing on the frontlines. One of the legal pathways we came across was the concept of “ecocide,” which is any unlawful or detrimental act that is committed despite the awareness that it will cause severe, irreversible, long-term damage to the environment. We also learned about the island nation of Palau, which in 2012 attempted to seek an advisory opinion from the International Court of Justice on the question of transboundary harm, but did not succeed.

What we want to see from the court is a progressive advisory opinion that speaks to and clarifies states’ obligations to protect the rights of present and future generations from the adverse effects of climate change. Not just stating those obligations, but speaking to them. And not shying away from saying there are legal consequences for not living up to them. We’re hoping for something transformative in terms of accountability, because the way we’re behaving now does not align with science.

© SPC

What might a favourable ruling mean for other vulnerable areas, like the Arctic?

Climate change affects all of us. That is a fact that we really want to sink in with every leader around the world. We asked the court to protect the entire climate system—and the Arctic obviously plays a very big part in this system. Although we speak from our experience in small island states, our work can benefit all regions, including the Arctic. Arctic people have been often left out of the conversation, but the International Court of Justice can provide all frontline communities with a tool—in terms of accountability and in terms of negotiations—to strengthen the mechanisms that already exist and bring us closer to climate justice.

By WWF Global Arctic Programme