© Mikhail Bondar

Energy modelling

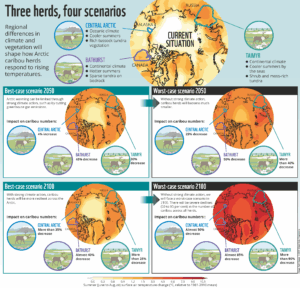

What the future may hold for Arctic caribou

There’s no question that a warmer climate is mostly bad news for Arctic caribou. By causing heat stress, increasing insect harassment in summer, and making it hard to find food after rain-on-snow events in winter, climate changes constitute a looming black cloud on the caribou’s horizon. On the other hand, warmer summers also benefit Arctic plants, especially shrubs—which means more food for caribou—and climate varies regionally across the Arctic.

So, just what does the future look like for migratory tundra caribou herds across the Arctic? The Caribou Futures project is trying to answer that question.

The WWF Global Arctic Programme asked two Canadian caribou biologists, Anne Gunn and Don Russell, to discuss the future of Arctic caribou in a warmer climate and specifically how regional climate variations and their effects on vegetation will influence how caribou herds respond.

“The project is trying to give us a glimpse into the future for different migratory caribou herds to see how they might develop under different climate change scenarios,” explains Ronja Wedegärtner, a project lead with WWF. “It’s also about giving policymakers and the public a sense of what to expect so they know how and where to act.”

Providing a snapshot of caribou’s future

Gunn and Russell examined how three migratory tundra caribou herds in different regions—with different climates and vegetation—might fare under best- and worst-case warming scenarios. Although they don’t have a crystal ball, the pair of biologists used a modelling tool built from field data collected by many people over decades.

“The model is unique—there is no other like it for caribou, or even for any other northern hoofed mammals. This is partly because of its detail, but mostly because it is the only model that considers both forage intake and energy output, such as the cost of seasonal movements or providing milk to a calf,” says Gunn, who coordinates the CircumArctic Rangifer Monitoring and Assessment Network, better known as CARMA, along with Russell.

The model calculates caribou energy budgets and forage intake to predict future caribou population trends under different climate change scenarios. By incorporating data from 50 years of research, it can assess a caribou herd’s food intake and translate it into the amount of energy and protein a caribou cow needs for activities like getting pregnant, growing a calf, producing milk, or replenishing reserves that get depleted during the winter.

Design: Ketill Berger, © WWF Global Arctic Programme

Looking at three key Arctic herds

To come up with their projections, Gunn and Russell used three representative migratory caribou herds: the Central Arctic herd on Alaska’s coast, the inland Bathurst herd in Nunavut, Canada, and the coastal Taimyr herd in Russia.

What they found was that, while all three herds will likely decline under both the best- and worst-case scenarios, the future doesn’t look the same for all of them.

The biologists modelled two global climate scenarios: the best-case scenario assumes strong global action to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, leading to slower warming and fewer extreme climate shifts. The worst-case scenario assumes emissions continue to rise, resulting in higher temperatures and more frequent extremes by 2100. Current global trends suggest we are closer to the higher-emissions trajectory, though future policy choices could still alter the path.

For caribou, one herd in the coastal Central Arctic initially fares well enough in the first decades of the optimistic scenario, but declines over the longer term. The Bathurst and Taimyr herds will likely decline under both scenarios, and the losses are steeper and more widespread in the worst case.

The Bathurst herd also faces a future in which a proposed road could run right through its migratory route

Mean monthly temperatures in the worst-case scenario will exceed historic maximums for all three herds by 2100. But the Bathurst herd will likely see the highest number of hot days—a jump from 9 to 95 days with temperatures higher than 20oC—as well as the highest rate of decline in herd size. That’s because higher temperatures mean increased insect harassment and more heat stress, reducing foraging time and making reproduction less likely.

The Bathurst herd also faces a future in which a proposed road could run right through its migratory route—which could be more bad news for the herd’s future.

“Through other work we have been doing in Nunavut, we were able to make some projections in terms of how a road is going to impact that herd. But then we add in the model’s projections for climate change, and we can see that climate is going to play a big role in the herd’s future,” explains Russell, who has studied caribou for almost 50 years.

Offering an urgent warning

Wedegärtner says it can be shocking to look at the projected herd numbers from the model outputs. “It’s really pointing a finger at the issue,” she says. “I think people know climate change is going to do something to caribou, but this project is giving them the space to imagine what that something could be—and from that comes the urgency to act.”

So is all hope lost for Arctic caribou? The simple answer is no. According to Gunn and Russell, there is still time to turn things around—if the world responds to the warnings.

Reducing emissions and the effects of climate change to the greatest extent possible will offer caribou herds across the Arctic the best chance.

“Since glacial times, caribou have been able to adapt to sweeping climate changes because of their ability to move to ranges where they can survive,” says Russell. “This tells us that managing roads and developments to keep them permeable to caribou movements is a key management tool to increase the adaptive capacity of caribou faced with a rapidly warming Arctic climate.”

It also comes down to greenhouse gas emissions. Reducing emissions and the effects of climate change to the greatest extent possible will offer caribou herds across the Arctic the best chance.

Still, the model outputs are a stark reminder of what is at risk for caribou—and the people who revere and depend on them—if we don’t act now.

By WWF Global Arctic Programme