© Erling Svensen / WWF

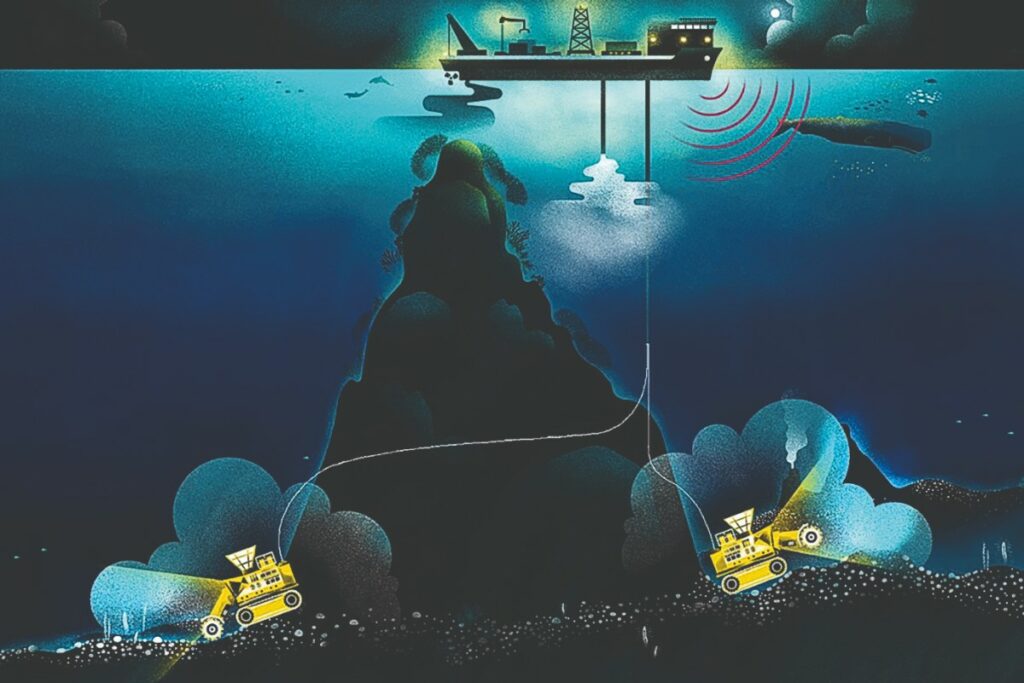

Deep sea mining

The shift from fossil fuels to increasingly electrify the global economy from clean energy sources is creating an ever-increasing demand for the materials that go into batteries or other new low emission products. Some of these materials are located on the Arctic seabed, in ecosystems that remain largely unexplored.

Why are we concerned?

The deep sea harbours a vast diversity of undiscovered species, essential for many ecosystem functions including climate regulation (carbon storage) and fisheries production. The deep sea covers over 90 per cent of the biosphere and is vital to local cultures and global well-being. However, deep-sea ecosystems, especially in the Arctic, face threats from the climate crisis, pollution, and bottom trawling. Deep-sea mining could exacerbate these pressures further, causing irreversible biodiversity loss, habitat destruction, sediment plumes, and the release of toxins and stored carbon. Underwater noise pollution and disrupted ecological processes also pose risks. The lack of scientific knowledge on deep-sea ecosystems and their services hinders understanding the full impact of mining. Consequently, a pause on deep-sea mining is the only way forward until more scientific information becomes available.

In the Arctic, in December 2023, the Norwegian government agreed with two opposition parties to proceed with plans of exploration of deep seabed mining in Norwegian waters. With this, Norway is set to be one of the first countries in the world (and first in the Arctic) to start the journey towards commercial mining the seabed for minerals. Rushing the exploration process and letting a potentially destructive industry disrupt the fragile and understudied deep sea ecosystem without addressing significant knowledge gaps is likely to have catastrophic consequences.

© WWF

What is needed?

Need to apply the precautionary approach

Deep seabed mining would pose significant risks to the ocean, including causing irreversible harm to the marine environments and its ecosystem services or the extinction of entire species. The scientific gaps related to the deep sea, including its ecosystems and species, are large and will take many years, if not decades, to fill.

Without such knowledge, impacts of deep seabed mining cannot be fully understood. This lack of scientific knowledge calls for a precautionary approach. Extraction must not go ahead until the environmental, social and economic risks are understood, all alternatives to deep-sea minerals have been explored and it is proven that deep-sea mining can be managed in a way that protects the marine environment and prevents biodiversity loss, habitat degradation and species extinction.

Need for consistency with relevant international policies and commitments

In light of the current status of scientific knowledge, the need to preserve biodiversity and to ensure the ocean’s resilience to the impacts of climate change, and to ensure consistency with global and regional commitments, there is a need to halt deep seabed mining now. Deep seabed mining would go against many of the commitments governments have made to each other, e.g., in the Sustainable Development Goals, as well as the newly adopted Global Biodiversity Framework and commitments to protect species).

Need for more knowledge to make science-based decisions

Today, scientists estimate that we have as little as 1.1 per cent of the knowledge required to make science-based decisions around whether deep seabed mining can go ahead. Knowledge of the polymetallic nodules, mineral-rich rock formations found on the deep ocean floor, is only just beginning to emerge. As knowledge such as this emerges, it becomes even clearer that deep seabed mining would be complicated and involve significant known and unknown risks, both for the marine environment and for the people who would be working on mining the minerals from the deep ocean.

What is WWF Global Arctic Programme doing?

© Jim Leape / WWF

Advocating for a circular economy

WWF urges governments to invest in a fully circular economy Instead of opening up a new frontier for extraction. The necessary transition to a fossil free economy, the ‘Green Transition’, does not need minerals from the deep sea. A 2022 report, The Future is Circular, commissioned by WWF, sets out pathways for how the switch to a fossil free economy can be done with less material footprint, avoiding opening up the deep sea to mining.

The report shows that demand for the studied seven critical minerals can be reduced by 58 per cent by technological choices, recycling and circular economy measures. Through product-life extension and materials recovery among others, governments can lead the way towards a “closed-loop” economy that works with nature, not against it.

© Bit Cloud / Unsplash

Shining a light on the Norwegian deep sea mining decision

Given the obligations outlined in various international instruments, it is highly likely that Norway’s deep seabed mining will face legal challenges in both national and international courts. It is already tarnishing Norway’s long-standing reputation as a leader in the global ocean agenda. And in an unprecedented move, the European Parliament raised a concern about the decision by the Norwegian Storting, calling for the adoption of an international moratorium. WWF Norway is suing the Norwegian government for opening its seabed to deep-sea mining, stating that Norway has not adequately investigated the potential consequences of this decision which violates Norwegian law, disregards the advice of its own experts, and sets a dangerous precedent.

Norway’s decision to proceed with deep-sea mining diverges from the stance of an increasing number of nations, including France, Ireland, Finland, Sweden, Canada, Kingdom of Denmark and the UK, which advocate for a ban, moratorium, or precautionary pause. Norway’s move also conflicts with its international commitments to ocean protection, including its pledge to sustainably manage coastal waters by 2025 and its participation in global initiatives promoting a sustainable ocean economy. Pursuing deep-sea mining contradicts these principles, raising doubts about Norway’s suitability for championing or even participation in such initiatives.